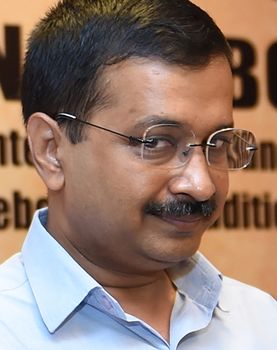

On the morning of March 11, as the counting of votes began, the official residence of Delhi Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal was all geared up to celebrate in anticipation of the Aam Aadmi Party’s grand forays into Punjab and Goa.

The lawn was done up with marigold flowers and tricolour balloons; huge LED screens were put up to beam results live; laddoos were ordered; and a big crowd of AAP workers had gathered outside the 6 Flagstaff Road residence, eagerly waiting to break into rhapsody. A large number of brooms—the party’s symbol—were also kept ready for revellers.

But, it was an anticlimax: the AAP ended up a poor second in Punjab (20 of 117 seats) and drew a blank in Goa.

Kejriwal, who was watching the results on TV, turned pensive. He wanted to be left alone; he was upset.

Had the AAP won in Punjab, Kejriwal would have emerged as the primary rival to Prime Minister Narendra Modi. And a few seats in Goa would have bolstered the AAP’s expansion plans. But the Goans, obviously, had other plans.

Unable to digest the drubbing—like Mayawati in Uttar Pradesh—Kejriwal blamed the electronic voting machines for the results. “Many people said there was anger against the Akalis, and the AAP was going to sweep the polls. Still, the AAP got 25 per cent votes and Shiromani Akali Dal got 31 per cent. How is this possible?” he asked. The AAP convener alleged that 20 to 25 per cent of his party’s votes were ‘transferred’ to the Akali Dal.

Kejriwal’s dejection is understandable. The AAP had invested a lot of effort in Punjab. The party had begun work on setting up base in the state early in 2015; Kejriwal had dispatched his A-team for the task. Some Congress leaders, in fact, admitted that they were worried whether Kejriwal would steal a march on them.

Punjab—which had given the thumbs up to the AAP even during the Modi wave in 2014—responded enthusiastically to the party’s campaign for the assembly polls. Kejriwal, who addressed a hundred rallies across the state, had made a terrific start with his speech at the Muktsar Maghi Mela. He promised the cheering crowd that he would end corruption and rampant drug menace, and punish the culprits who desecrated the Guru Granth Sahib in November 2015.

The AAP, however, frittered away this early advantage. Its rivals called Kejriwal and his party “outsiders”. A series of mistakes made by the party cemented that tag. For one, the AAP blundered by putting the Broom alongside the Golden Temple on its manifesto for youth.

Also, the Punjab leadership of the AAP was unhappy with the dominance of the Delhi unit. The sidelining of its Punjab convener Sucha Singh Chhotepur, who later turned against Kejriwal, proved costly.

Notably, the AAP did not declare a chief ministerial candidate. It also did not deny reports that Kejriwal would shift base to Punjab if the party won there. Kejriwal, a Haryanvi, would never have been accepted by Punjabis as their chief minister.

To top it all, the party welcomed questionable elements in its zeal to win, inviting criticism that it was pandering to pro-Khalistan entities.

Now, rivals call the AAP a one-time wonder. But, party leaders disagree. Says AAP leader Ashutosh: “We are disappointed with the results. However, we are at number two position despite being a new party, and that is no mean achievement.”

The AAP’s next big test is in Delhi, in the municipal elections next month. The AAP has already splashed the city and media space with state government ads.

Kejriwal, who wished to take on Modi at the national level, would do well by focusing on the civic polls for now.