Raimon Panikkar, the philosopher polymath, who spent years in Banaras and taught at Harvard, was a scholar interested in the way we formulate problems. Panikkar often hinted that the difficulties of a problem often reside in the way it is formulated. To put it simply, the way we construct it might straitjacket the way we think. Given the nature of definitions, problem solving in this context becomes self-defeating. The violence is almost self-inflicted. What Panikkar observed wisely was particularly true of the way we construct problems around religion and democracy. Words like secularism, faith and belief become filters preventing us from seeing more complex realities.

The worlds of religion and politics are often constructed as an either/or. In a modernist age, we often act as if we can have one or the other. As a result of such dualist proclivity, we tend to freeze oppositions and embalm categories. Rarely does our dualistic thinking recognise ambiguity, irony, paradox, or even the creativity of interaction. In sanitising categories, we sanitise a world, emptying out the possibilities of emergence.

In India, any discussion on religion and democracy gets caught between two incommensurable dogmas, the choice between secularism and communalism. Indian electoral politics, throughout the Congress years, ran on this grid. The dualism was so officially stark that our secularism became politically correct and empty. Politics became hypocritical as parties tried to hide religious beliefs and interests in a closet. This led to the labelling of the Congress as pseudo-secular. It also led to a hyper-rationalism which sought to attack superstition without exploring the limits of rationalism itself. India, as a country with roots in Islam, Hinduism, Jainism and Sikhism, ignored the creative possibilities of syncretism. Worse, as a country, we imported secularism without understanding its genealogy. As the political scientist William Connolly said—secularism arose in history as a parochial solution between two Christian sects. The tragedy was that we tried to globalise it. What we also forgot is that our secular imagination cannot provide a base for public ethics in ecology, or for responses during tragedies in which compassion loses to disaster fatigue. A Pope Francis can respond to the Syrian crisis while secular Europe refuses the entry of refugees.

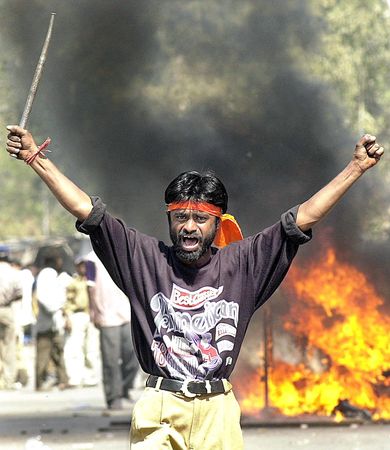

The dominance of the religious world view or majoritarian religious view also constricts democracy. First, majoritarian religion tends to concede little to minorities, who survive by making concessions. Secondly, majoritarianism becomes a collection of vigilantist epidemics policing sexuality, body, food and diet, controlling other religions as an everyday ritual. Majoritarian religion also becomes violent, and small occasions of misunderstanding explode into major riots, all of which serve injustice. Whether it is the riots in Mumbai 1992-1993, Delhi 1984, Gujarat 2002, Muzaffarnagar 2013, the victim waits, afraid to be either citizen or believer. Democracy loses twice by failing to guarantee the right to belief and the right to be different. A communalist mindset creates a wave of programmes which ensures that minorities can never be at ease when riots become a form of ethnic cleansing. A simple statistic from Economic and Political Weekly shows that more than 1 million people have been displaced by ethnic riots, almost all with a religious edge. When we attempt to grasp that next to development projects, riots are the biggest source of displacement, the challenge to the open-ended democracy of the future becomes painfully clear.

Democracy in India becomes caught between two straitjacket solutions, each of which adds to the problem. We are caught between an impoverished secularism and an overwrought communalism. Each acts with a piety and righteousness which makes deliberation different. When belief is tied to electoral votes, rational decision making becomes difficult. The logic of electoralism makes secular thought uneasy, allowing it to teeter to one minoritarian edge or the other. Secularism also tends to be aridly statist and uniform, emptying India of the sheer diversity and plurality of its imagination. In a biographical sense, it is often a young mass belief. Secularists like Nehru or Chandra Shekhar had their ashes sprinkled on the Ganges, affirming at least a cosmic solidarity.

As a philosopher, a believer, a translator, as someone deeply concerned with the ecumenical, involved with a dialogue of religion, which also involves a dialogue of secularisms, Panikkar felt the current impasse of modernity was straitjacketing democracy. Instead of becoming a festival of beliefs which shifted kaleidoscopically, democracy was becoming an arid electoral calculus. In his various works, he drew a distinction between three ways of looking at and constructing the world.

He gave them a slightly esoteric twist to ensure, like another philosopher Charles Peirce suggested, that they were not kidnappable or misused for the wrong purposes. He dubbed them ontonomy, autonomy and heteronomy. The meanings were simpler. Autonomy is a condition which includes the exclusion or the independence of separate spheres of being. Thus Religion and Politics are separated. Religion as belief and activity is confined to the private sphere. Economics and Politics belong to the public domain. Secularism thus believes in the separation of spheres of activity.

Riot and wrong: A Bajrang Dal activist during the 2002 riots in Ahmedabad. A communalist mindset creates a wave of programmes which ensures that minorities can never be at ease when riots become a form of ethnic cleansing | AFP

Riot and wrong: A Bajrang Dal activist during the 2002 riots in Ahmedabad. A communalist mindset creates a wave of programmes which ensures that minorities can never be at ease when riots become a form of ethnic cleansing | AFP

The second possibility was heteronomy, which allows the predominance of some spheres of activity over the other. In a theocratic society like Khomeini’s Iran, religion dominates all other spheres of activity. Such theocracies are heteronomous. Politics as the state can also dominate religion, as in Kemal Ataturk’s Turkey. State sponsored secularism dominates all sectors of life, even invading the private. The French attempt to erase the veil in public life is another such form of secularist interference. Both kinds of society, while transformative in the beginning, have an authoritarian strain. Democracy can claim few odds in such a system.

Panikkar suggested a third possibility. He first alludes to heteronomy as a phase closely associated with the Middle Ages, and suggests that the autonomy accompanied the humanist critique of religion. The writer then speaks of ontonomy. Ontonomy, he claims, is act of non-violence where each sphere unfolds and mingles with other spheres without doing violence to itself or to the other. It allows creativity, dialogue and interaction. It is the middle way of the Buddha. The historian A.L. Basham gave a brilliant example when he said medicine in India was never communalist, the physicians discuss their theologies and their theories of cure, their technique of healing, the sense of limits with great enthusiasm. Panikkar claims ontonomy allows for a mutual fecundation. It allows for “a mutual understanding and fertilisation of distinct fields of human activity without rupturing harmony”. Ontonomy allows for emergence, surprise, diversity and syncretism, conditions which democracy desperately needs to be inventive. Instead of the orderly regimes, where categories are policed, domesticated or even panopticonised, ontonomy allows for creative disorder without being subject to the hierarchies of thought. It allows a congregation of myriad possibilities.

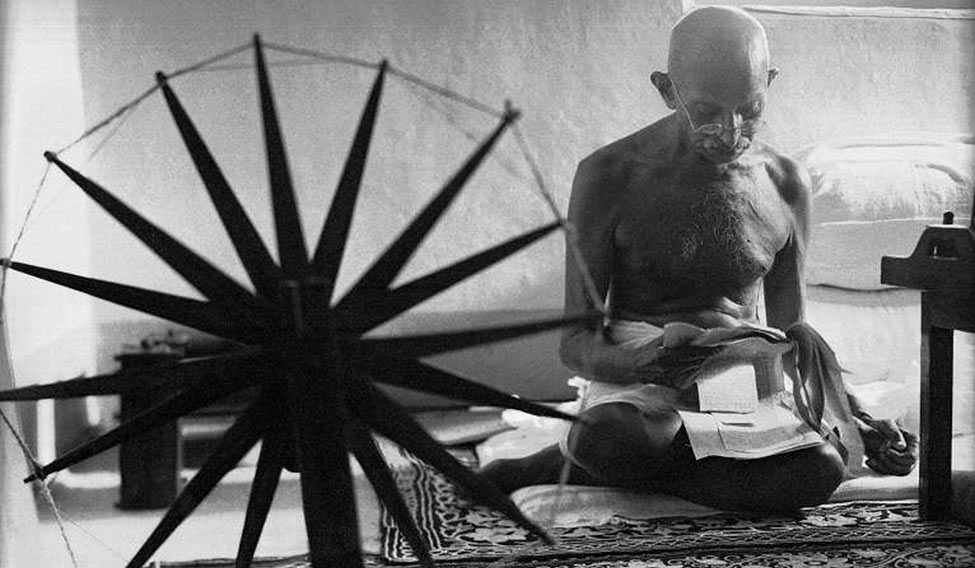

India, one feels, is a society that has struggles with all three possibilities. The Nehruvian world saw an attempt to create a secular nation state which failed as an electoral imagination. The rise of the BJP created an electoral theocracy where majoritarian Hinduism has sought to suppress Muslim and other minoritarianisms. Despite the best of intentions, both have rendered democracy arid. Both have operated within a nationalist substrate. Ontonomy, however, is more civilisational; it seeks a mingling of selves and ideas. Sufism has always had that touch of syncretism and so has the bhakti movement. Gandhi gave a touch of syncretism to all his religious thinking. He also considered himself a scientist performing ethical experiments. Ontonomy helps sustain a sense of the sacred, a sense of scale and limits without which ecology would not be possible. Sacred groves and religious myths do more for ecology than any economics of sustainability.

India needs ontonomic thinking, which is neither scientism or fundamentalism, to remain inventive. An inventive democracy going beyond stereotypes, sensitive to the rigidity of categories, is critical. In fact, this might be hopefully India’s great contribution to modernity.

Shiv Visvanathan is professor, Jindal Global Law School and director, Centre for Study of Knowledge Systems, O.P. Jindal Global University.