A rose by any other name would smell just as sweet, sighed a rather lovesick Juliet. Dr A.P.J. Abdul Kalam would not agree. Sweet, heady and fragrant was his favourite. His roses were not beautiful until he could bury his nose in and breathe the almost sugary smell.

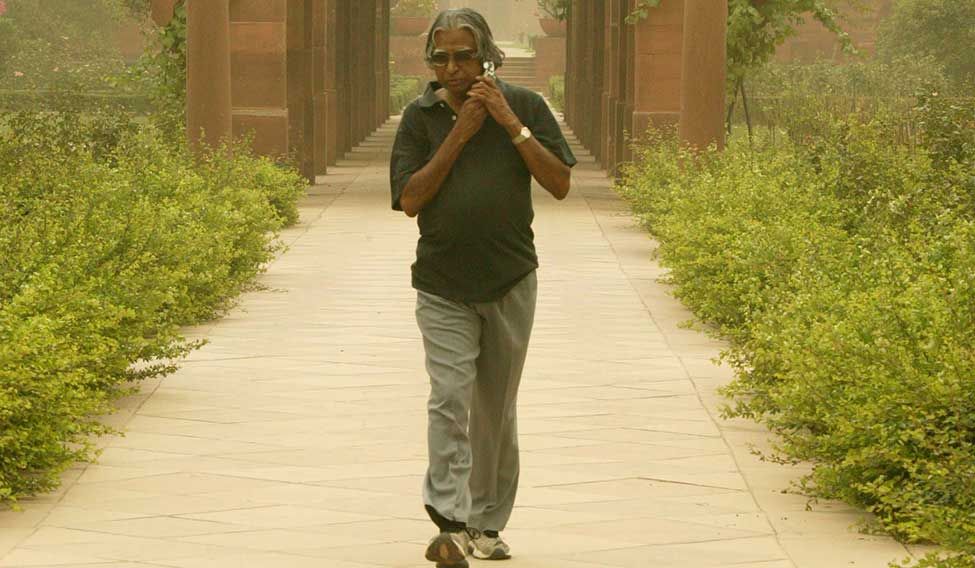

Roses of various shades—barbie pink, deep blood-red, crimson and sunshine yellow—scattered across the sandstone paths in the Mughal Garden. Kalam sahib, as he was known at the Rashtrapati Bhavan, had a small meditation hut built in the garden. Kalam's old colleague Brahma Singh, who was special officer on deputation to the Rashtrapati Bhavan, once sent word to him that there was a rose worth seeing in the garden. “He came down immediately, looked at the flower and stuck his nose in it. He then told me, ‘I don’t think this is beautiful. It has no smell.’ I got the message,” said Singh.

The hunt for the perfect rose then became a mission. Saplings were sent for from Bengaluru, Pusa and Kolkata to create a rose that was the complete package. Kalam’s dream has now become a possibility. “Scientists have identified the gene which is responsible for the smell,’’ said Singh, who later continued his experiments with Kalam at the former president's Rajaji Marg residence in Delhi.

Lessons from Kalam often came wrapped in philosophical fables. “Each religion holds different plants as sacred. We planted seeds of plants worshipped in Hinduism and Islam in the same pit. His idea was that if they grew together, why couldn’t we,’’ said Singh.

Kalam threw open the sprawling presidential estate to an audience of millions. Simple, warm and disarmingly friendly, he stayed up nights reading, but never caused any inconvenience to anyone. A household attendant who was attached to him said Kalam never complained about anything. “He ate whatever was served. He never made a request or asked for anything special,’’ he said. The only questions he had were about our children. “'It is important that you educate them', he would tell us. 'They are the future of our country.' We worked for him. But he treated us as family.”

Often, he would eat on the move. His lunch break never lasted for more than 20 minutes. While on a trip to Bihar, Kalam broke protocol and went to the lunch area meant for the presidential staff. He would often ask the military secretary accompanying him to make sure that the photographers and journalists present at his functions had their meals.

He loved music. During a concert in the Mughal Garden, Pandit Hariprasad Chaurasia who was playing, asked the audience to identify a tune. Kalam was the first to raise his hand.

“When he wanted to talk to you, he would pick the phone and call you directly,’’ said Rashtrapati Bhavan chief photographer Samar Mondal. “It was always Mondalji. If he saw you, he would extend his hand and greet you,” said Mondal. “Sometimes he would call me in the middle of the night to find a picture. He would be waiting for me at his apartment and would offer me peanuts the moment I reached. ‘Mondalji eat', he would say.”

Kalam's tours were hectic. Once on a sweltering summer day, he had 23 engagements in his itinerary. He attended all of them and came back home at 3am. Flying out in the middle of the night never deterred him, despite the gingerly objections of the Air Force. He wanted to fill in each moment with as much as he could.

A bowl of peanuts was always on his desk to give him the energy to work through the nights. In the morning, he would sometimes gaze through his windows at the peacocks in the garden. “Once he summoned me at 5:30 in the morning,” said Mondal. “I arrived at the apartment to see him looking at a peacock from his window. ‘This guy is very nice,’ he said. ‘Go take a picture. He always dances for me while I sip my morning tea. Whenever you feel like you are in pain, you should take pictures of birds in nature. You will find that the pain is gone.'”

These simple truths are what the staff at the Rashtrapati Bhavan remember the most. They have an abundance of such stories—of dancing peacocks, the wisdom of children, the mysticism of nature and the boundless curiosity of a man who refused to be regulated by protocol.

“He never took credit for anyone else’s work,” said a staff member. “If a child told him something, he would insist on taking the child’s name and would say what he told him. He was really different.”