Reckoned from Plassey, the British ruled and looted India for 190 years. Counting from Warren Hastings, 42 governors-general and viceroys–a few acting–ruled India. Much as Indians resented their rule and their plunder, none of them was assassinated.

For the sake of a blood-soaked record, Lord Mayo, remembered thanks to a college in Ajmer, was knifed by a loony convict while the viceroy was visiting the Andamans. The man had no political motive; so Mayo’s murder is not counted as an assassination.

Left-leaning revolutionaries had thrown bombs at viceroys—at Lord Hardinge while he was entering the new capital, Delhi, in 1912; and at Irwin’s train while he was travelling from Calcutta to inaugurate New Delhi in 1929. But historians have wondered whether the assailants intended to kill the principals, or only wanted to scare the empire. Even Bhagat Singh’s intended target was Superintendent James Scott, who had baton-charged Lajpat Rai to death; it was by mistake that he killed young John Saunders. He did not intend to kill anyone when he hurled pamphlets and what were no more lethal than smoke-bombs in the central legislature.

Such individual incidents of violence were acts of individual revenge perpetrated on individual officers who had acted unjustly or vindictively—Udham Singh’s murder of Michael O’Dwyer, the butcher of Amritsar; Khudiram Bose’s bid on Magistrate Douglas Kingsford, and so on. Often they killed the wrong persons—Khudiram’s bomb spared Kingsford, but killed two women; the bomb hurled at Hardinge killed an Indian servant; and Bhagat killed Saunders instead of Scott. A few other killings, such as at Kakori or Chittagong, happened during raids on armouries or treasure trains. There was no intent to kill.

Yet, the British, though having legated a liberal jurisprudential system, hanged the perpetrators. Bhagat’s trial violated all norms of fair trial under English law, and he was hanged disregarding Mahatma Gandhi’s pleas for pardon. Irwin justified his rejection of Gandhi’s pleas, saying he was preventing the Mahatma from deviating from the path of nonviolence! Praise the Lord for small mercies!

The fact remains that the Indian political ethos, unlike what Gandhi would have wished, was not nonviolent all along. There have been violent outbursts of individual and popular anger against colonial conquerors, which remain as blood-smeared milestones on the otherwise nonviolent road to freedom.

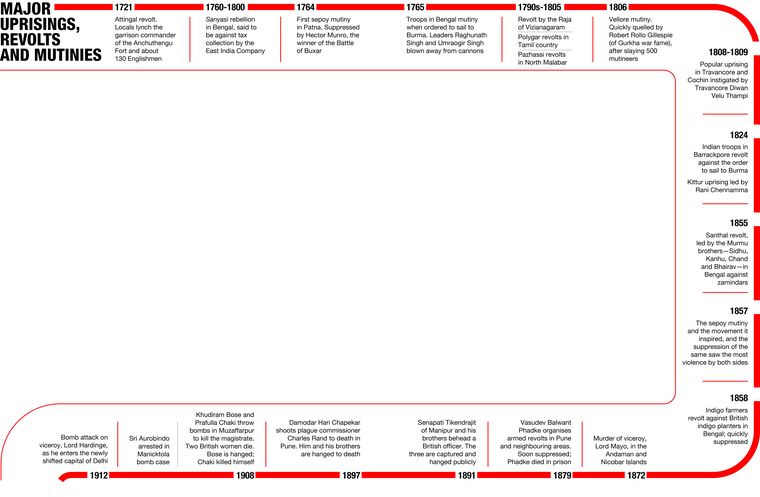

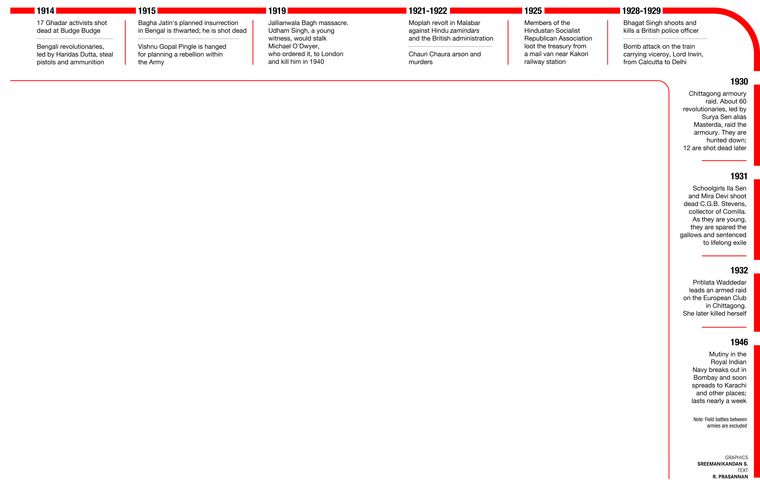

The frequency with which these milestones appear (see graphics) makes one wonder: was the path to freedom actually non-violent? The mainstream narrative of the freedom movement, authored by Gandhi, Jawaharlal Nehru, Vallabhbhai Patel, Maulana Azad, Gopal Krishna Gokhale, Bal Gangadhar Tilak and others, has been a saga of non-violence. They abhorred or abjured violence and, as we will see in the Chauri Chaura story, acts of violence reinforced their faith in nonviolence.

That saga of nonviolence has been told and retold. So have been the tales of battlefield valour—of dowager ranis like Chennamma and Lakshmibai, aged heroes like Kunwar Singh, hill guerilla chiefs like Pazhassi Raja, folk leaders like Veerapandiya Kattabomman, princely resisters like Tikendrajit Singh. We also know the stories of the controversial Tipu Sultan, the valiant Tantia Tope, the elusive Nana Saheb, as also the individual acts of bravery of Bhagat, Rajguru, Sukhdev, Azad, Khudiram Bose, the Chapekar brothers and others–men who scared the empire with pistol shots.

Also read

- Ahead of Aug 15, Vice President Venkaiah Naidu takes stock of India’s long journey

- Is BJP’s effort to revive memories of 1922 Chauri Chaura revolt a poll ploy?

- Fearlessness, discipline, communal harmony―the big lessons from Kakori martyrs

- How 356 sepoys of Bhopal contingent defied begum, British to set up a parallel govt

- Attingal revolt was among earliest acts of resistance against British imperialism

- Anjengo’s Eliza

- The real story behind Sanyasi rebellion

- Revisiting sites that shaped Indian polity

What has not been told enough are the stories of the angry common folk. Those who took part in little uprisings, often without leaders.

On this diamond jubilee of independence, THE WEEK looks at five landmark uprisings by the ordinary folk–the Attingal revolt, the sanyasi rebellion, the Sehore rebel raj, the Chauri Chaura riot and the Kakori raid. Each has been selected with care so as to represent a particular style and philosophy of revolt that is distinct from another’s.

If Attingal was the first recorded armed uprising against the British, the sanyasi or fakir rebellion was the first challenge to the right of the Company Bahadur to collect taxes. Sehore’s Sipahi Bahadur Sarkar was a unique attempt by a brigade of soldiers at erecting a native state system on captured territory. Chauri Chaura, the centenary of which will be observed next year, was perhaps the last outburst of folk violence before the Gandhian doctrine of nonviolence captured mass imagination. Kakori, on the contrary, was the best planned plunderous raid by a gang of idealists on the Alibaba caves of the raj.

Each had its own impact on the national sentiment. One could say, there was no national sentiment when the Attingal folk revolted 300 years ago. They did not shake any empire. All the same, the aftermath of the revolt weakened the feudal order of barons and martial arts-skilled knights in south Kerala, and led to the rise of a national monarchy in Travancore under Marthanda Varma.

Breaking out in the wake of the East India Company establishing a state system in Bengal, the sanyasi rebellion, the cause and conduct of which is a matter of dispute, could have been the first challenge to the regime’s right to collect taxes. It also inspired the first perfect novel in India, and gave birth to what would be free India’s national song.

The Sehore insurrection of 1857, though started as a sepoy war, was different from the revolts in the Ganga-Yamuna doab. The revolts in Meerut, Delhi, Kanpur, Lucknow, Jhansi and elsewhere were a series of battles between John Company’s loyal regiments on the one side, and the baronial armies of Nana Saheb, Tope and Lakshmibai joining forces with the rebel regiments. Sehore, on the other hand, was an attempt by the revolutionary troops to carve out a new territorial state; they sought no princely legitimacy nor military generalship from elsewhere.

The national movement, as we understand it today, was born in the years after the revolt. The ruthless suppression of the revolt had the effect of drilling into Indian minds the futility of waging armed battles against the raj. Considered the peaceful afternoon of the raj by the British, the latter half of the 19th century witnessed hardly any anti-colonial strife in India. The last war with a princely state had been fought in the 1840s with the Sikhs; and the last challenge, the great revolt, had been suppressed, leaving the British free to wage wars in Afghanistan, Burma, Persia, South Africa and Crimea, and day-dream of a lasting empire under Pax Britannica.

Indeed, there were attempts by idealists like the Haryana hero Rao Tula Ram, who travelled out to seek the help of the Amirs of Afghanistan, the Shah of Persia and the Tsar of Russia, to throw out the British. (Subhas Bose would follow in his footsteps in the 20th century.) These attempts reached nowhere. The imperial subjects resigned to a process of petitioning; the masters responded with patronising but parsimonious constitutional reforms. There were sporadic shocks delivered to the day-dreamers–such as the Poona insurrection and the Chapekar brothers’ murder of two British officers, but the period remained largely peaceful.

Lord Curzon’s partition of Bengal at the turn of the century changed all that. This most unimaginative political move by any ruler after 1857 ‘revolted’ both the Hindu and Muslim folk across India. Like Jallianwala Bagh a decade and half later, it exposed the Englishman’s perfidy to the masses who had come to imbibe his ideals of liberal democracy and judicial fair play. Bengal plunged into turmoil, with more of the common folk—as distinct from the feudal elite who had been waging wars and the educated elite who had been petitioning—taking to violence. Though the partition was annulled six years later, the national anger that it had unleashed could not be contained.

Voices of restraint were still heard from the likes of Gokhale, but they felt increasingly helpless against the continued perfidy of the British. The 1909 Minto-Morley reforms, the cheating on promises of post-World War I political concessions, the humiliation felt by the Muslims over the dissolution of the Turkish caliphate, the massacre of innocents at Jallianwala Bagh, and the disappointment with the 1919 Montagu-Chelmsford reforms undermined the moderates’ cause.

Gandhi appeared at this juncture preaching nonviolence, not as an option of the weak but as an article of faith, and seeking to involve not just the common folk but also the depressed classes, in the national movement. Underlying his non-cooperation call was a historic reality: that every regime–Maurya or Gupta, Pratihara or Paramara, Khilji or Tughlaq, Mughal or British–had ruled with an unexpressed consent, or splendid indifference, of the masses. By asking the masses to stop cooperating with the raj, Gandhi was urging them to withdraw that consent, or end their indifference. He was giving every Indian a stake in India’s governance.

Chauri Chaura was his first test. As he called off the movement in the wake of the violence saying India was not ready for peaceful struggle, every other leader, including Nehru and Patel, warned him against calling off the battle after unleashing the troops. Gandhi took it as a test of his own leadership–could he, like a general, call back his phalanxes after they had charged ahead, and then redeploy them?

Miracle of miracles! Gandhi succeeded.

The phase of violent mass uprisings ended with that. The few incidents of violence that India witnessed afterwards were individual acts, which, too, had their role in weakening the will of the rulers. The bomb bid in the central legislature by Bhagat and comrades, the attempt on Irwin’s train, the raid on the treasure train at Kakori, the attack on the Chittagong armoury were attempts at disrupting the smooth system of the colonial administration. The incidents unnerved the rulers, as much as did the Gandhian attempt at withdrawing cooperation with the regime, and then willfully breaking its laws.

Subhas Bose’s attempt at seeking a military solution as the World War clouds gathered was a hark back to the early period of military resistance. The defeat of the Axis powers in the war, largely with the help of Indian troops, put paid to his dreams. However, the move to prosecute his troops as mutineers outraged India so much so that the British were forced to grant them pardon.

Though Bose’s attempt failed, it kindled a rebellious military spirit among Indians. As that spirit burst forth in a communist-inspired naval mutiny, national leaders realised that it could have disastrous consequences on the constitutional stability of independent India. They intervened to pacify the rebels.

But the mutiny had rung alarm bells across the empire. The British realised it was wiser to heed to the national leadership, and let the sun set peacefully on their raj.

As it rose on an August morning 75 years ago on a new dominion, which would turn itself into a grand democratic republic led by a galaxy of the finest statesmen found anywhere in the post-colonial world, there were also marks of mass violence appearing ominously on the territorial horizons of a partitioned Bharatvarsh.