After faculty members of the Indian Institute of Technology Delhi recently evaluated the semester examinations answer sheets, institute director Professor V. Ramgopal Rao asked for volunteers who were willing to have the same scripts evaluated by computers. The answers were subjective type, written in paragraphs. The idea was to see whether machine evaluation was as good as that done by examiners.

Decades after the essay-type questions gave way to multiple-choice and objective-type ones, primarily in entrance tests, technology may help bring back the long answers and possibly extend them to subjects that typically did not need them. Thanks to technology, artificial intelligence and machine learning are making steady inroads into higher education in different ways. One of the early determinants of its efficacy could be the comparison of AI-driven paper evaluation with IIT’s internal manual evaluation.

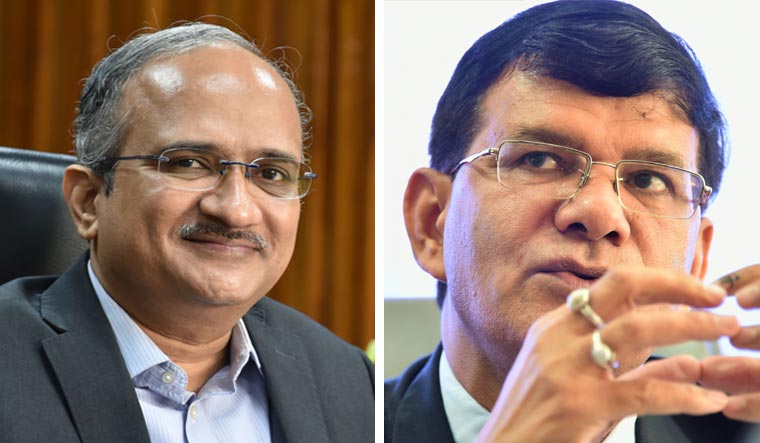

“A subjective kind of paper will test the creativity of students. Right now, we test analytical ability,” said Rao. With successful and satisfactory implementation of AI-based techniques for subjective evaluation, he says they will be able to set papers which can “test the human being in his full form”. “It is possible that the syndrome of mugging or learning by rote may end, but I do not want to overemphasise that it will solve all our problems,” he said. The speed of evaluation will be unmatched, given the number of students and the limited time.

“The next wave of reforms in this country will have to come in the examination system,” said Professor Raj Singh, vice-chancellor, Ansal University, Gurugram. “We have to have a variety of methods of evaluation. Learning has to be taken to the level of creating or making. That has to be the highest level of learning outcome, and we have to be able to evaluate that. Using AI in evaluation is a very important issue.”

Ansal intends to use AI differently from the IITs. The university expects to map a student’s performance from the beginning of the course till the end, in periods of four to five months, instead of just once at the end of the semester. The various schools in Ansal also expect to capture how the student assimilated knowledge, along the way, of other disciplines that are involved in creating a final product or service. This, Singh says, is not possible to capture in the current evaluation system.

The IIT’s decision of trying out AI/ML-based evaluation of subjective answers got a push at the deans’ committee meeting a few months ago. IITs are already in talks with companies that can provide solutions. “We are evaluating and will probably start something on a trial basis next semester for internal evaluation,” said Rao.

It stands to reason that other technical institutes and design schools will soon follow suit if the method proves to be successful. As for liberal arts and humanities, it is expected to take longer.

“Digital initiatives are happening, but we have still a long way to go,” said Professor John Varghese, principal, St Stephen’s College, New Delhi. Everything was done with pen and paper till three months after he took charge as principal in 2016. A lot of paper applications had gone missing, and so an e-filing system was introduced, capturing all the data—photographs, marks, certificates, interests, academic and even family details—of students admitted. The principal says that it has had a positive impact on the college environment and green spaces. Only 28 per cent of the campus has construction on it, and the idea of having more buildings to store papers is not what they want.

But using technology for evaluation is something they would not consider. Not for now, at least. “Even if we go technologically forward, we would not want to bring in those for evaluation because this is a very human effort, where the children answer questions. It is not done mechanically,” said Varghese.

Nevertheless, there are companies working full time to build programmes that will enable computer evaluation of creativity. But AI-based evaluation will have to go through more screening processes before they are applied for national examinations, and these start-ups are not yet ready for such operations.

There is another issue that Rao expects the AI-based evaluation to address. “Question paper setting is an involved process,” he said. “We get worried if a student gets 100 out of 100. We set papers at a certain level to challenge the students. Students getting 100 is a failure of the examiners. We need to challenge the students.” AI-driven evaluation is expected to reduce the number of centums. The fallout will be that examinations are bound to become even more difficult.