Adil Ahmad Dar—who blew himself up to hurt the Indian military—was a follower of Sufism. As a member of the Barelvi movement of Islam, which espouses Sufism, believes in saints and visits to shrines, Dar did not fit the profile of a suicide bomber. In police records, he was listed as a category C militant, far below the more lethal A++ or A+ ones.

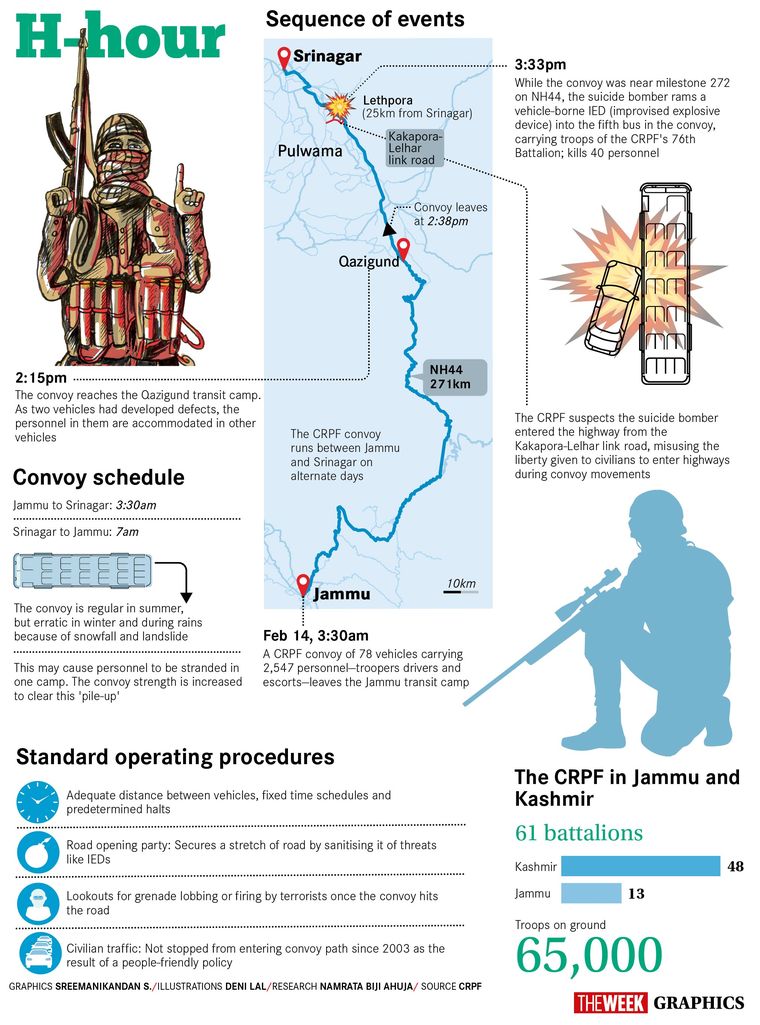

Not many knew of Dar outside his village of Gundibagh, in Pulwama district of Jammu and Kashmir, until February 14. On the fateful Thursday, Dar crashed an explosive-packed vehicle into a Central Reserve Police Force convoy at Lethpora in Pulwama, killing 40 personnel and injuring several others. The CRPF convoy of 78 vehicles, carrying 2,547 personnel, had left for Srinagar from Jammu early in the morning, in regular vehicles. As a rule, after crossing Jawahar Tunnel, the occupants move into bulletproof bunker vehicles at Qazigund in Anantnag, south Kashmir. But on that day, as the convoy was larger than usual, only a part of it could be moved into bunker vehicles. The heavy snowfall and landslides in the state had forced the closure of the Srinagar-Jammu highway, and many CRPF jawans had been stuck in Jammu. As their periodic deployment had not been possible because of the weather, large convoys were used to transport them en masse to Srinagar. Notably, on February 4, another convoy of 91 vehicles, carrying 2,871 personnel, had reached Srinagar from Jammu safely.

Investigators, including a team of the National Investigation Agency, the state police and experts from the Central Forensic Science Laboratory, collected samples of the debris of the targeted bus for forensic analysis. They found the bumper of a red Maruti Eeco, which Dar was driving, a metal piece and parts of a jerry can, in which about 30kg of explosives could have fit.

Dar had reportedly used a service road to pull up beside the convoy, which stretched up to a kilometre, and had targeted the fifth vehicle. The bus was reduced to a blackened metal frame. So powerful was the explosion that people in the nearby cluster of shops, selling saffron and dry fruits, fled in panic. Some parts of the bus were strewn as far as 150 meters away, smelling of blood and burnt flesh. Some jawans in another bus were also injured, and the convoy came to a halt after the attack. Many jawans ducked for cover thinking they were under fire. When they got down to check what had happened, they saw bits of their brothers’ bodies on the road.

Jaish-e-Mohammad took responsibility for the attack and released a pre-recorded video clip of Dar, in which he says: “By the time this video reaches you, I’ll be enjoying in heaven. This is my last message to the people of Kashmir. Jaish has kept the fire alive. Come and join the group and prepare for one last fight.”

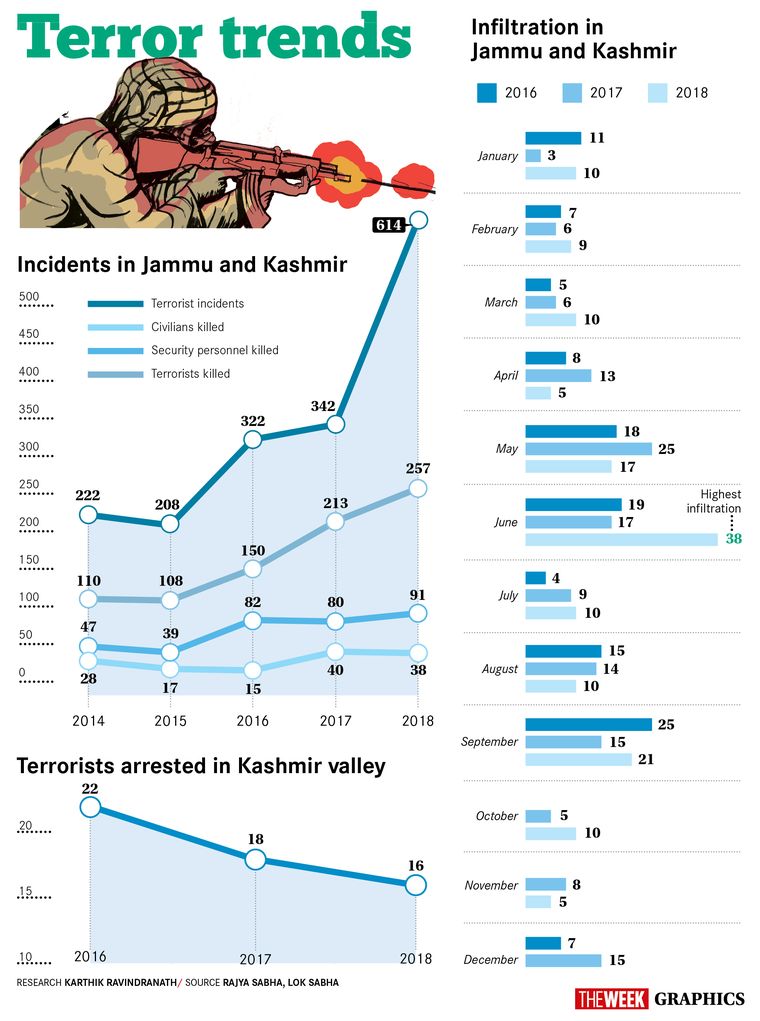

The attack happened in the wake of security forces killing more than 250 militants, over half the number believed to be active in Kashmir, in the past one year. Of these, 18 were most wanted and 207 were locals.

Usually, suicide bombings are carried out by Islamist groups that follow the Salafi (Islamic State) and Deobandi (Taliban) sects of Islam. JeM also follows the Deobandi ideology, and such Islamist groups consider some of the Barelvi practices un-Islamic.

Perhaps that is why Dar’s family and neighbours could not believe he had become a suicide bomber, and accepted it only after they saw his video. As they did not have a body to bury, the villagers in Gundibagh held a symbolic funeral prayer. A relative said the police told Dar’s family, “What is there to hand over for burial,” implying that the body had been torn to bits.

Amid curbs on movement by security forces, THE WEEK reached the village to find out how the boy—who believed in Sufism, sang Naat (poetry in praise of the Prophet), helped his mother in daily chores, and worked as a painter and labourer to earn a living—became a suicide bomber.

The police and CRPF had barricaded the bridge that leads to Gundibagh. Small groups of men were huddled together along the last stretch of the potholed road that led to Dar’s house, which was surrounded by paddy fields. Ghulam Hassan, Dar’s father, sat with a few neighbours in a small room on the ground floor. “He quit studies after class 12 and worked at a bandsaw mill for some time,” he told THE WEEK. “I saw him only once after he joined militancy last year. I have no idea why he chose to become a militant. The SHO (station house officer) called and said he had done it.”

In another room, Dar’s mother, Fahmeeda, was saying her prayers as neighbours consoled her. “I desperately wanted him to give up militancy,” she shouted amid sobs. “We tried hard but we did not succeed.”

Imtiyaz Ahmed Dar, a relative, said the teenage Dar never betrayed signs of becoming a militant. In fact, at times, he would confront those who held radical views about Islam. A neighbour, who did not want to be named, said the whole village was stunned. “Barelvis do not talk much about jihad and martyrdom,” he said. “I fail to understand how someone like him could do it.” Whispers in the village, however, say Dar was transformed after security forces gunned down Hizbul Mujahideen commander Burhan Wani in 2016. The killing led to an uprising in which 116 people, mostly youth, were killed and thousands were injured. Dar, too, had been injured, taking a bullet to his leg in the uprising, said another neighbour. “His cousin was a militant. He, too, was killed in 2016,” he said.

A boy outside Dar’s house told THE WEEK that the police had once forced Dar to rub his nose on the ground when he was returning from school. Hassan, who later said that he felt the pain of the CRPF jawans, recalled that the police incident had made his son feel humiliated.

Another neighbour said that though Dar followed Sufism, he had a radical strain in him. “Once he and his friends beat up a policeman who was travelling with a woman in a car outside the village,” he told THE WEEK. “They thought the couple was indulging in vice. The man said he was a policeman but they did not care.”

One of Dar’s distant relatives told THE WEEK that Dar and his best friend Sameer, who was pursuing his masters degree, joined militancy together, and though JeM and Lashkar-e-Taiba has no presence in Gundibagh, Sameer might have had some links with JeM.

Former director general of police Shesh Paul Vaid, who led the police during the 2016 protests, agreed that Burhan’s killing had a role in the radicalisation of Kashmiri youth, especially through social media. “The use of a local boy for a suicide attack is to give it a local colour. It suits Pakistan,” he said.

Though the number of local militants swelled after the 2016 uprising, most of them proved to be sitting ducks for the security forces; they did not have training or weapons. In the past two years, more than 450 have been slain close to their homes in south Kashmir, and many in the state called it a “massacre” on social media.

To counter the security forces’ offensive, JeM sent a large group of suicide bombers into Kashmir from Poonch in the summer of 2017. Among them were Tahla Rasheed and Usman Ibrahim, nephews of JeM chief Masood Azhar. They then moved to south Kashmir where they met the four-foot-tall Noor Trali, the JeM commander out on parole after eight years in jail. He helped them move to different areas of south Kashmir in small groups and launch attacks. Trali also indoctrinated local boys Fardeen Khanday and Manzoor Baba of Pulwama, and they would soon execute his vision.

On December 31, 2017, the two, along with a Pakistani militant, launched a suicide attack on a CRPF camp at Lethpora, in which five jawans were killed. The attack happened three days after Trali, 47, was killed in an encounter at Samboora in Pulwama.

It was for the first time in 17 years that locals had launched a suicide attack in Kashmir, and this set alarm bells ringing in the security circles in Kashmir and Delhi. The attack happened after security forces had killed Azhar’s nephews in encounters a few weeks earlier. To avenge them, JeM sent Afghan war veteran Abdul Rasheed Ghazi, an expert in making improvised explosive devices (IEDs), along with two others to Kashmir. Reportedly, Ghazi was the mastermind of the February 14 attack.

He was killed two days after the Pulwama attack, along with another JeM militant Fahad, also a Pakistani, and a local militant Hilal. Five Army personnel, including a major, were also killed in the encounter.

On February 19, at a news conference, Lt Gen K.J.S. Dhillon, the 15 Corps commander, said: “I would like to inform the nation that in less than 100 hours of the Pulwama terrorist attack, we have eliminated the JeM leadership in the valley. Anyone who picks up guns in Kashmir will be eliminated unless they surrender. This is a message to all the mothers of Kashmir,” he warned. He added that JeM was a “child” of the Pakistani army and they, as well as the Inter-Services Intelligence, had a role to play in the February 14 attack.

Since the attack, security forces have reverted to the pre-2003 protocol of not allowing any civilian traffic on the highway when a convoy is on the move. They have also restarted checking of vehicles and frisking of passengers travelling in public transport, which has not gone down well with Kashmiris.

K. Rajendra Kumar, former Jammu and Kashmir DGP, said JeM has remerged as a major threat. “It emerged as a threat in 2000 for some time and then other groups like Lashkar-e-Taiba were active,” he told THE WEEK. “The JeM then became active again and formed Afzal Guru squads [to avenge his death].” Kumar, who was injured in an LeT suicide attack on a Youth Congress rally in Srinagar in 2006, said terrorists attack when nothing is happening. “The key to defeating them is not getting complacent when the situation seems normal,” he said.

What is worrying the security forces is whether vehicle-borne IED attacks, like the one carried out by Dar, would be the new trend.

The real challenge, however, remains the radicalisation of the youth, as seen in Dar’s viral video. “The war that they cannot win with force, they are trying to win by compromising your belief,” he says. “They want to mislead you from the path of Islam by luring you with worldly pleasures.”

And that is what makes JeM dangerous. It is the only group that has successfully brainwashed local boys into become suicide bombers. The LeT does not carry out suicide attacks, and especially not those involving explosive-laden vehicles. The LeT considers suicide attacks un-Islamic. But it carries out fidayeen attacks, which are technically suicide missions, but with a chance of survival.

Security forces have prevented LeT attacks with a mix of technology, fortification of camps, raising barbed fences, use of CCTV cameras and increasing vigilance. However, stopping a suicide bomber is a much harder task.