Ravindra Yadav runs a popup food cart at Delhi’s Sarojini Nagar market. Two months ago, Yadav’s desi-Chinese fare was so popular that it clocked sales of more than Rs 1 lakh a day, and he barely got time to sit or check his phone from 11am to 8pm.

All that has changed since the demonetisation of Rs 500 and Rs 1,000 notes on November 8 last year. Sales are now so poor that, for the past few days, he has been seriously thinking about returning to his village in Haryana. With the fall in the number of people flocking to markets like Sarojini, his income has dwindled to a fourth of what he had been making, and he worries about prompt repayment of loans he had taken to invest in the business. “From 300 to 350 customers a day, I am down to 100 customers,” he says. “My entire business was running on cash, and now I don’t have enough to pay my helper.”

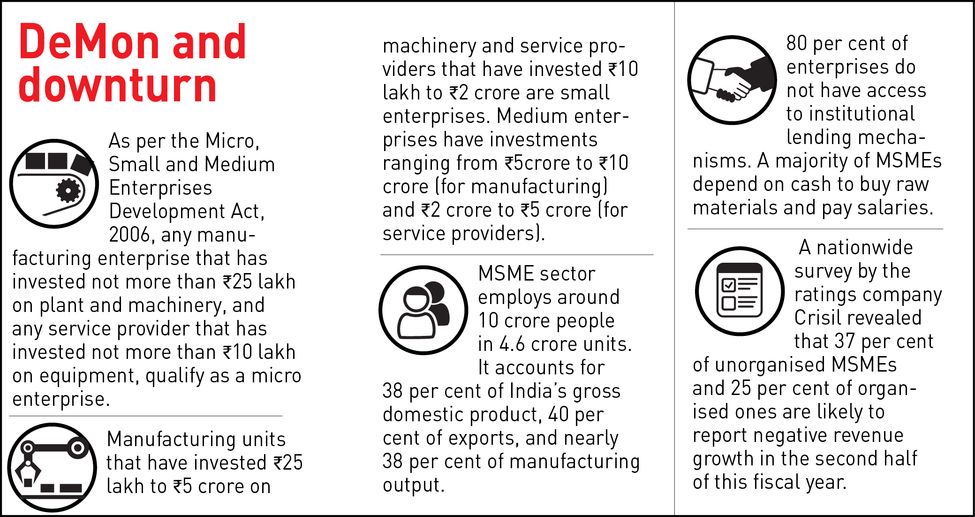

While stories of the common man facing difficulties because of demonetisation are aplenty, it is micro enterprises such as Yadav’s that are worst affected. There are about four crore micro enterprises in the country, of which 80 per cent do not have access to institutional lending mechanisms. “Bank credit is available only to a small percentage of the MSMEs [micro, small and medium enterprises],” says Rajiv Chawla, president of Faridabad Small Industries Association. “Most of them borrow through informal channels. Banks do not lend them for lack of collateral. Now, as money has dried up in the system, micro enterprises are feeling squeezed.”

Moving them to a cashless system is a tall order, as they are part of an ecosystem that works on cash. Yadav does not know about Paytm and has never gone to a bank. “The entire micro enterprises segment which was running on cash has come to a standstill,” says Chawla. “That does not mean that they were doing something unethical or generating illegal money. In the hunt for crocodiles, the fish are bearing the brunt.”

Take the case of Salunkhe Packaging Pvt Ltd, a small company in Mumbai. Its business has gone down by 45 per cent over the past two months. “Corporates are not getting orders for their products, therefore demand for packaging has also come down. Earlier, we used to pay in cash for raw material as suppliers would release the order only after confirmed payment. Now we are paying by demand draft, but it slows down the process,” says Chandrakant Salunkhe, managing director of the company and president of SME Chamber of India.

Another difficult part, says Salunkhe, is paying salaries of labourers. “They prefer salary in cash and many of them do not have a bank account. A lot of migrant labourers are leaving and, these days, it is tough to find a casual labourer. Once demand picks up, it will be difficult for us to keep up with the production, because we have lost almost 20 per cent of casual workers.”

Chawla’s company, Jairaj Ancillaries, which manufactures auto components, has seen a severe demand slowdown with auto sales crashing by 40 per cent. Chawla has been trying hard to get accounts opened for his workers, but many of them do not have ID proof as they migrate from one state to another. “We have paid them in instalments, but still lost 40 workers,” he says.

The famed brass industry of Moradabad in Uttar Pradesh shows how cash is deeply entrenched in the way small industries function. The raw material for brass is supplied by people who deal in scrap. They sell scrap to the consolidators, who buy it in cash and often handle the next three to four stages in production. The scrap is melted and turned into brass silli (slab or bar). The next stage involves making moulds—of a flower vase or a tap, for instance. The brass is melted and poured into these moulds.

After this stage, the craftsmen who make designs take over. Then comes the stage of polishing and lacquering. Each stage depends on cash transactions. Thereafter, the brass products come into the distribution network. That, too, works on cash.

As underreporting revenues is common in the sector, experts say demonetisation will force companies to fall in line with the regulatory regime. “The government is trying to push them to go to the next level by being compliant,” says Sankar Chakraborti, chief executive officer of SMERA Ratings, a rating services provider. “That will result in higher declared profits and will translate to investments in capacity expansion. SMEs will have to clean up their operations and introduce technology into manufacturing, financial transaction management and customer development.”