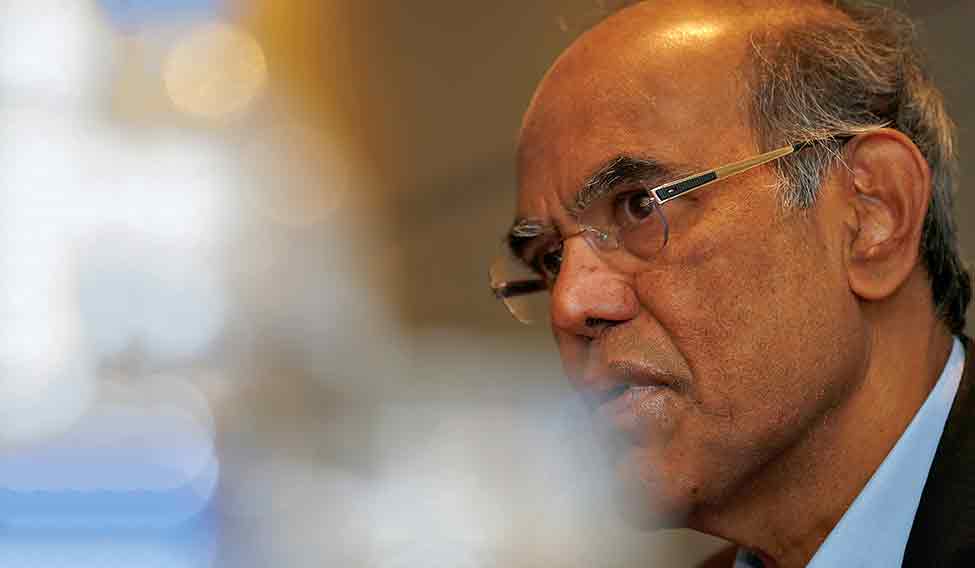

When Y. Venugopal Reddy's term as Reserve Bank governor was about to end in September 2008, there was speculation about who would succeed him—just as there has been so much speculation about who would succeed Raghuram Rajan, who retires next month. On Reddy's retirement, Duvvuri Subbarao, the finance secretary then, became Reserve Bank's 22nd governor. The global meltdown took place days after he assumed office and by the time India recovered from it in 2009, inflation was raging.

“To appreciate the severity of inflation during this period, you only need to note that the average wholesale price index (WPI) inflation during the three-year period 2010 to 2012 was 8.7 per cent, significantly higher than the average inflation of 5.4 per cent during the entire previous decade (2001-2010)”, Subbarao writes in Who Moved My Interest Rate?: Leading the Reserve Bank of India Through Five Turbulent Years. Subbarao changed the interest rate a record 13 times in 18 months from October 2011 and confesses that he was nicknamed “Baby Step Subbarao” by those who thought he did so timidly, most often by a quarter of a per cent.

Excerpts from an interview with the author:

Is it possible for a governor to implement his own priorities?

As long as the governor's priorities sync with the priorities of the institution and those of the larger macro scenario, the governor can set the agenda.

Can you give me an example for this?

The outreach programme. The governor, the top management of the RBI and the entire RBI team were involved in it. I encouraged them to visit villages and understand the ground situation rather than simply read reports and analyses.

What was the result of this?

It helped the RBI to understand the ground reality and whether the inflation had gone up. We could see to what extent banking services were available to those in the villages and the quality of it. We were able to hear them out on how they feel about inflation and jobs. And also about how difficult they found it to transfer money.

Is there a difference between the autonomy of the governor and the autonomy of the RBI? Why is this autonomy important?

There is no difference because the governor does not have any autonomy independent of the institution that he heads. The RBI must have autonomy to maintain price stability which is necessary for sustainable growth. Monetary policy is largely about finding a balance between the requirements of growth and the requirements of managing inflation and in this, there will always be some tension between the government and the Central bank. What is important is that there should be some mechanism to manage this tension.

Why is the conflict between growth and inflation never-ending?

If you have a situation where growth is high and rapid and inflation is low and steady, that is a Goldilocks situation. This is ideal but we have hardly had that consistently… maybe for very short periods. Governments, particularly in democracies, want to highlight growth because that is a way of creating jobs which, in turn, make people feel good. But growth which comes at the cost of price stability is not sustainable.

You may have interacted with your predecessors for this book. What has been their experience?

There has always been some differences between the RBI and the government on the calibration of the monetary policy; and the way these differences were managed has been different during the tenures of different governors.

What do you think about the new Monetary Policy Committee (MPC)?

I believe it is a good move to shift decision-making from the governor—an individual—to the collective wisdom of a committee chaired by the governor. But I only feel that the government is implementing it in an abrupt manner. The transition period should be longer.

What should be the term of a governor?

Five years will give a governor the time to implement all the reforms and initiatives he has started.

You have raised the issue of purity of data, almost suggesting that data is suspect.

Real-time data was inaccurate and there were many revisions of it. But when there are many fluctuations in growth and inflation, as it happened during my time, the deviations in data become more prominent. I don’t know whether there were data deficiencies before, but during my tenure, it played a bigger role in wrong-footing policy formulations.

Would a government want to tamper with such figures?

I don’t think so... It is very farfetched and highly improbable. Seeing any political motivation for this is wrong; it should be seen purely from a technocratic perspective. The figures were not doctored.

How does the RBI get its data?

The RBI gets data from the Central Statistical Organisation (CSO), and also does some independent surveys—of inflation expectations, corporate performance, credit off-take, corporate outlook and purchase plans. So the RBI tries to correlate data from the CSO with its own surveys and tries to make as intelligent an estimation of the true state of affairs as it can.

Did you foresee the problem of non-performing assets (NPAs)?

Yes, the problem started during my tenure. There were always some NPAs but their steep rise started during my time. It was the result of a number of factors. First, the restructuring done during the crisis. Second, some corporate exuberance upon the opening up of the infrastructure sector, investment in which was, to some extent, uncharted territory. Third, the inability of banks to assess the projects objectively because it was a new territory for them also. Then there were the delays in the implementation of the projects because of government policies.

Low interest rates hurt many…

There is a constituency that benefits from high interest rates. The savers, for instance. The RBI does try to ensure that savers get a real rate of return on their savings; also because maximising savings is a macro-economic objective; the larger the domestic savings the less our dependence on foreign savings.

Who would fit the role of an RBI governor better—a bureaucrat or an economist?

You can’t stereotype like that. It depends on the individual. In theory, you can have anyone, but in practice, the person should have some understanding of macro-economics and Central banking. You also need to understand the dynamics of globalisation.

What will be the challenges of the next governor?

There will be many. But the biggest challenge will be to institutionalise the new monetary policy framework, the statutorily-backed inflation targeting framework and the institution of the MPC because the conventions, practices and protocol that are now established will have a long-term impact on monetary policy formulations.

Would it worry you to have telecom operators running banks?

It is better that they are in the recognised banking space and regulated by the RBI than be outside it and doing banking.