Partway through Alex Gibney’s earnest documentary, Steve Jobs: The Man in the Machine, an early Apple Computer collaborator named Daniel Kottke asks the question that appears to animate Danny Boyle’s recent film about Jobs: How much of an a------ do you have to be to be successful? Boyle’s “Steve Jobs” is a factious, melodramatic fugue that cycles through the themes and variations of Jobs’ life in three acts—the theatrical, stage-managed product launches of the Macintosh computer (1984), the NeXT computer (1988) and the iMac computer (1998). For Boyle (and his screenwriter, Aaron Sorkin) the answer appears to be “a really, really big one.”

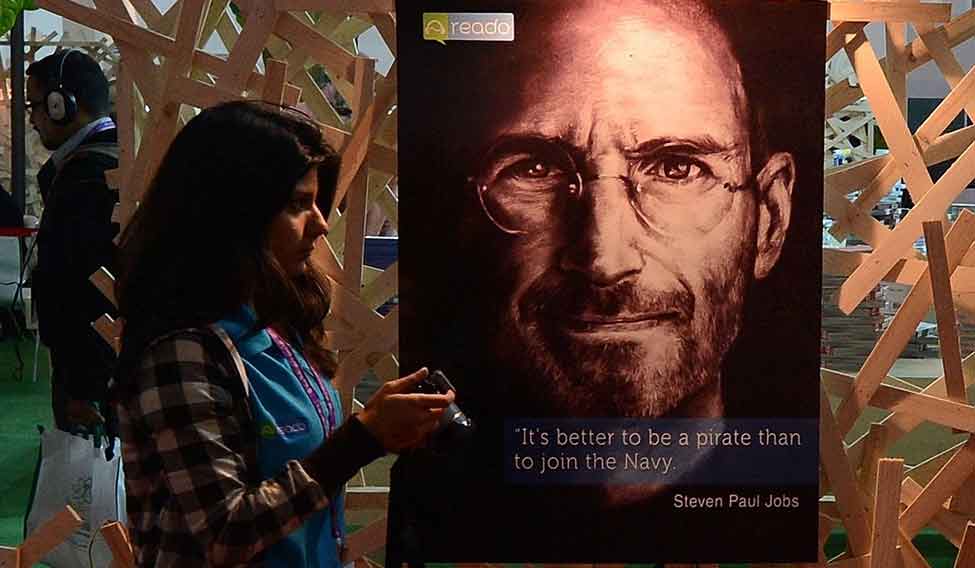

Gibney, for his part, has assembled a chorus of former friends, lovers and employees who back up that assessment, and he is perplexed about it. By the time Jobs died in 2011, his cruelty, arrogance, mercurial temper, bullying and other childish behaviour were well-known. So, too, were the inhumane conditions in Apple’s production facilities in China—where there had been dozens of suicides—as well as Jobs’ halfhearted response to them. Apple’s various tax avoidance schemes were also widely known. So why, Gibney wonders as his film opens—with thousands of people all over the world leaving flowers and notes “to Steve” outside Apple Stores the day he died, and fans recording weepy, impassioned webcam eulogies, and mourners holding up images of flickering candles on their iPads as they congregate around makeshift shrines—did Jobs’ death engender such planetary regret?

The simple answer is voiced by one of the bereaved, a young boy who looks to be 9 or 10, swiveling back and forth in a desk chair in front of his computer: “The thing I’m using now, an iMac, he made,” the boy says. “He made the iMac. He made the MacBook. He made the MacBook Pro. He made the MacBook Air. He made the iPhone. He made the iPod. He’s made the iPod Touch. He’s made everything.”

Yet if the making of popular consumer goods was driving this outpouring of grief, then why hadn’t it happened before? Why didn’t people sob in the streets when George Eastman or Thomas Edison or Alexander Graham Bell died—especially since these men, unlike Jobs, actually invented the cameras, electric lights and telephones that became the ubiquitous and essential artifacts of modern life? The difference, suggests the MIT sociologist Sherry Turkle, is that people’s feelings about Jobs had less to do with the man, and less to do with the products themselves, and everything to do with the relationship between those products and their owners, a relationship so immediate and elemental that it elided the boundaries between them. “Jobs was making the computer an extension of yourself,” Turkle tells Gibney. “It wasn’t just for you, it was you.”

In Gibney’s film, Andy Grignon, the iPhone senior manager from 2005 to 2007, observes that “Apple is a business. And we’ve somehow attached this emotion [of love, devotion and a sense of higher purpose] to a business which is just there to make money for its shareholders. That’s all it is, nothing more. Creating that association is probably one of Steve’s greatest accomplishments.”

Jobs was a consummate showman. It’s no accident that Sorkin tells his story of Jobs through product launches. These were theatrical events—performances—where Jobs made sure to put himself on display as much as he did whatever new thing he was touting. “Steve was P.T. Barnum incarnate,” says Lee Clow, the advertising executive with whom he collaborated closely. “He loved the ta-da! He was always like, ‘I want you to see the Smallest Man in the World!’ He loved pulling the black velvet cloth off a new product, everything about the showbiz, the marketing, the communications.”

Whether to protect trade secrets, or sustain the magic, or both, Jobs was adamant that Apple products be closed systems that discouraged or prevented tinkering. This was the rationale behind Apple’s lawsuit against people who “jailbroke” their devices in order to use non-Apple, third-party apps—a lawsuit Apple eventually lost. And it can be seen in Jobs’ insistence, from the beginning, on making computers that integrated both software and hardware—unlike, for example, Microsoft, whose software can be found on any number of different kinds of PCs; this has kept Apple computer prices high and clones at bay. An early exchange in Boyle’s movie has Steve Wozniak arguing for a personal computer that could be altered by its owner, against Jobs, who believed passionately in end-to-end control. “Computers aren’t paintings,” Wozniak says, but that is exactly what Jobs considered them to be. The inside of the original Macintosh bears the signatures of its creators.

The magic Jobs was selling went beyond the products his company made: It infused the story he told about himself. Even as a multimillionaire, and then a billionaire, even after selling out friends and collaborators, even after being caught backdating stock options, even after sending most of Apple’s cash offshore to avoid paying taxes, Jobs sold himself as an outsider, a principled rebel who had taken a stand against the dominant (what he saw as mindless, crass, imperfect) culture. You could, too, he suggested, if you allied yourself with Apple. It was this sleight of hand that allowed consumers to believe that to buy a consumer good was to do good—that it was a way to change the world. “The myths surrounding Apple is for a company that makes phones,” the journalist Joe Nocera tells Gibney. “A phone is not a mythical device. It makes you wonder less about Apple than about us.”

It’s important to remember that when Jobs was forced out of Apple in 1985, the two computer projects into which he had been pouring company resources, the Apple 3 and another computer called the Lisa, were abject failures that nearly shut the place down. A recurring scene in Boyle’s fable is Jobs’ unhappy former partner, the actual inventor of the original Apple computer, Wozniak, begging him to publicly recognise the team that made the Apple 2, the machine that kept the company afloat while Jobs pursued these misadventures, and Jobs scornfully blowing him off.

Jobs’ second act at Apple, which began either in 1996 when he returned to the company as an informal adviser to the CEO or in 1997 when he jockeyed to have the CEO ousted and took the reins himself, propelled him to rock-star status. True, a few years earlier, Inc. magazine named him “Entrepreneur of the Decade,” and despite his failures, he still carried the mantle of prophecy. It was Jobs, after all, who looked at the first home computers, assembled by hobbyists like his buddy Wozniak, and understood the appeal that they would have for people with no interest in building their own, thereby sparking the creation of an entire industry. (Bill Gates saw the same computer kits, realised they would need software to become fully functional and dropped out of Harvard to write it.) But personal computers, as essential as they had become to just about everyone in the ensuing two decades, were, by the time Jobs returned to Apple, utilitarian appliances. They lacked—to use one of Jobs’ favourite words —“magic.”

Back at his old company, Jobs’ first innovation was to offer an alternative to the rectangular beige box that sat on most desks. This new design, unveiled in 1998, was a translucent blue, oddly shaped chassis through which one could see the guts of the computer. (Other colours were introduced the next year.) It had a recessed handle that suggested portability, despite weighing a solid 38 pounds. This Mac was the first Apple product to be preceded by the letter “i,” signaling that it would not be a solitary one-off, but instead, in a nod to the burgeoning World Wide Web, expected to be networked to the Internet.

And it was a success, with close to 2 million iMacs sold that first year. As Schlender and Tetzeli tell it, the iMac’s colorful shell was not just meant to challenge the prevailing industry aesthetic but also to emphasise and demonstrate that under Jobs’ leadership, an Apple computer would reflect an owner’s individuality. “The i [in iMac] was personal,” they write, “in that this was ‘my’ computer, and even, perhaps, an expression of who ‘I’ am.”

Jobs was just getting started with the “i” motif. (For a while he even called himself the company’s iCEO.) Apple introduced iMovie in 1999, a clever if clunky video-editing program that enabled users to produce their own films. Then, two years later, after buying a company that made digital jukebox software, Apple launched iTunes, its wildly popular music player. iTunes was cool, but what made it even cooler was the portable music player Apple unveiled that same year, the iPod. There had been portable digital music devices before the iPod, but none of them had its capacity, functionality or, especially, its masterful design.

Michael Fassbender plays Steve Jobs in the film, directed by Danny Boyle. "Steve's obsession is where we're going, not where we've been," Boyle says.

Michael Fassbender plays Steve Jobs in the film, directed by Danny Boyle. "Steve's obsession is where we're going, not where we've been," Boyle says.

According to Schlender and Tetzeli, “The breakthrough on the iPod user interface is what ultimately made the product seem so magical and unique. There were plenty of other important software innovations, like the software that enables easy synchronization of the device with a user’s iTunes music collection. But if the team had not cracked the usability problem for navigating a pocket library of hundreds or thousands of tracks, the iPod would never have gotten off the ground.”

By 2001, then, Apple’s strategy, which had the company moving beyond the personal computer into personal computing, was underway. Jobs convinced—or, most likely, bullied—music industry executives, who had been spooked by the proliferation of peer-to-peer Internet sites that enabled people to download their products for free, into letting Apple sell individual songs for about a dollar each on iTunes. This, Jobs must have known, set the stage for the dramatic upending of the music business itself.

Apple’s reach into the music business was fortified two years later when the company began offering a version of iTunes for Microsoft’s Windows operating system, making iTunes (and so the iPod) available to anyone and everyone who owned a personal computer. Providing a unique Apple product to Microsoft, a company Jobs did not respect, and that he had accused in court of stealing key elements of the Mac operating system, only happened, Schlender and Tetzeli suggest, because Jobs’ colleagues persuaded him that once Windows users experienced the elegance of Apple’s software and hardware, they’d see the light and come over from the dark side. In view of Apple’s recent $1 trillion valuation, it looks like they were right.

The iPod, as we all know by now, gave way to the iPhone, the iPod Touch and the iPad. At the same time, Apple continued to make personal computers, machines that reflected Jobs’ clean, simple aesthetic, brought to fruition by Jony Ive, the company’s head designer. Ive was also responsible for the glass and metal minimalism of Apple’s hand-held devices, where form is integral to function. Mobile phones existed before Apple entered the market, and there were even “smart” phones that enabled users to send and receive email and surf the Internet. But there was nothing like the iPhone, with its smooth, bright touch screen, its “apps” and the multiplicity of things those applications let users do in addition to making phone calls, like listen to music, read books, play chess and (eventually) take and edit photographs and videos.

Jobs’ hunch that people would want a phone that was actually a powerful pocket computer was heir to his hunch 30 years earlier that individuals would want a computer on their desk. Like that hunch, this one was on the money. And, like that hunch, it inspired a new industry—there are now scores of smartphone manufacturers all over the world—and that new industry begot one of the first cottage industries of the 21st century: app development. Anyone with a knack for computer programming could build an iPhone game or utility, send it to Apple for vetting and, if it passed muster, sell it in Apple’s app store. These days, the average Apple app developer with four applications in the Apple marketplace earns about $21,000 a year. If someone were writing a history of the “gig economy”—making money by doing a series of small freelance tasks—it might start here.

Gibney begins his movie wondering why Jobs was revered despite being, as Boyle’s hero says of himself, “poorly made.” (In the film, he says this to his first child, whose paternity he denied for many years despite a positive paternity test, and whom he refused to support, even as she and her mother were so poor they had to rely on public assistance.) Gibney pursues the answer vigorously, and while the quest is mostly absorbing, it never gets to where it wants to go because the filmmaker has posed an unanswerable question.

And, here is another: With one new book and two new movies about Jobs out this season alone, why this apparently enduring fascination with the man? Even if he is the business genius Schlender and Tetzeli credibly make him out to be, the most telling lesson to be learned from Jobs’ example might be summed up by inverting one of his favorite marketing slogans: Think Indifferent. That is, care only about the product, not the myriad producers, whether factory workers in China or staff members in Cupertino, or colleagues like Wozniak, Kottke and Tevanian, who had been crucial to Apple’s success.

iPhones and their derivative hand-held i-devices have turned Apple from a niche computer manufacturer into a global digital impresario. In the first quarter of 2015, for example, iPhone and iPad sales accounted for 81 per cent of the company’s revenue, while computers made up a mere 9 per cent. They have also made Apple the richest company in the world. The challenge, now, as the phone and computer markets become saturated, is to come up with must-have products that create demand without the enchantments of Jobs.

Apple’s release of Siri, the iPhone’s “virtual assistant,” a day after Jobs’ death, is as good a prognosticator as any that artificial intelligence and machine learning will be central to Apple’s next generation of products, as it will be for the tech industry more generally. (AI is software that enables a computer to take on human tasks such as responding to spoken language requests or translating from one language to another. Machine learning, which is a kind of AI, entails the use of computer algorithms that learn by doing and rewrite themselves to account for what they’ve learned without human intervention.)

Jobs had an abiding belief in freedom—his own. As Gibney’s documentary, Boyle’s film and even Schlender and Tetzeli’s otherwise friendly assessment make clear, as much as he wanted to be free of the rules that applied to other people, he wanted to make his own rules that allowed him to superintend others. The people around him had a name for this. They called it Jobs’ “reality distortion field.” And so we are left with one more question as Apple goes it alone on AI: Will hubris be the final legacy of Jobs?

(Sue Halpern is a scholar in residence at Middlebury. Her latest book is A Dog Walks into a Nursing Home).

Steve Jobs: The Man in the Machine: a documentary film directed by Alex Gibney

Steve Jobs: A film directed by Danny Boyle

Becoming Steve Jobs: The Evolution of a Reckless Upstart into a Visionary Leader: By Brent Schlender and Rick Tetzeli

Pages: 447; price: Rs2,030 approx.