“The illegitimate offspring of retreating imperialism.” Back in the late 1990s at Delhi's Jawaharlal Nehru University, this was how one of our professors used to describe Israel. The basis of his argument was that the conception of the state of Israel was based on the Balfour Declaration, an imperial guarantee offered by the preeminent colonial power of the time. For the Jews, the declaration by the British government was the first formal international guarantee in support of a “national home”. It can, however, also be seen as the root cause behind the Arab-Israeli conflict as the proposed national home was to come up in Palestine, a territory which had an Arab population above 90 per cent.

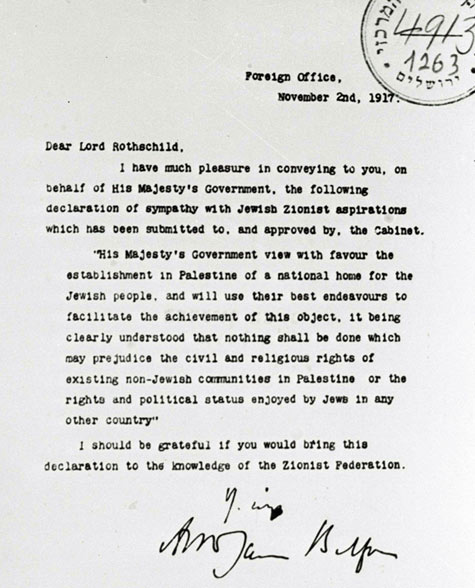

The declaration, dated November 2, 1917, came in the form of a letter written by the British foreign secretary Arthur Balfour to Baron Lionel Walter Rothschild, the leader of the Jewish community in Britain. Said the letter:

“His Majesty's government view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, and will use their best endeavours to facilitate the achievement of this object, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country.”

The first official endorsement of a state exclusively for Jews served as a major boost for the Zionist campaign. Yet, even after hundred years, a question still remains. Was Britain qualified enough to give such a promise? Or was it just a part of routine gamesmanship employed by great powers?

At the time of the Balfour Declaration, Palestine was part of the Ottoman empire and Britain had no locus standi in the territory. World War I (1914-18) was going on and Britain, along with its allies France and Russia (the US joined later) were fighting Germany, Austria-Hungary and the Ottomans. To weaken the Ottomans, Britain undertook negotiations with Hussein bin Ali, the Sharif of Mecca, to lead an Arab revolt in Palestine against their Ottoman overlords. In return, it offered to recognise an Arab state in the region with Hussein as the king. On June 5, 1916, the Arabs launched their revolt against the Ottoman sultan.

[File] A copy of the Balfour Declaration | AFP

[File] A copy of the Balfour Declaration | AFP

Roughly at the same time, Britain was in secret talks with France and Russia to carve out spheres of influence in the Ottoman Arab provinces outside the Arabian peninsula for themselves. Known as the Sykes-Picot agreement [it was signed by Sir Mark Sykes, a British diplomat, and Francois Georges-Picot, a French diplomat], it was not known to the Arabs or the Zionists. So, when the Balfour Declaration offered the Jewish people a national home, the British government was referring to a land ruled by the Ottomans, one which was already offered to the Arabs, and which it ultimately intended to keep for itself.

For the Zionist movement, however, the Balfour Declaration was an unqualified success. It accepted, at least in principle, the Zionist demand for a state although the vague term “national home” was used. However, its import was quite clear. It would be a land where the Jews would enjoy privileged rights. All references in the declaration were framed favouring the Jews. For instance, it spoke of guaranteeing the “civil and religious rights” of “non-Jewish communities in Palestine” and that, too, only of “existing” ones. It failed to take note of their political rights and was silent about their descendants and immigrants. Second, it spoke of the non-Jewish communities as if they were in a minority in Palestine, although in 1917 they constituted more than 90 per cent of the population.

The promise, however, was not given as an official document or charter, instead as a private letter to a private citizen. Moreover, it did not offer Palestine as the “national home” for Jews, but said that a “national home” would be established there. Yet, the letter give a major fillip to the nationalist dreams of the Zionists.

The Zionist victory capped several months of diligent diplomatic and political efforts in London and several other European capitals and, of course, the United States. After Theodore Herzl, the father of the Zionist movement, launched the World Zionist Organisation with the aim of setting up an independent state for the Jews because of the pervasive anti-Semitism in Europe, several territories, including one in British east Africa, were considered for the purpose. However, a majority of the Zionist leaders were in favour of establishing the state in Palestine because of historical and religious reasons.

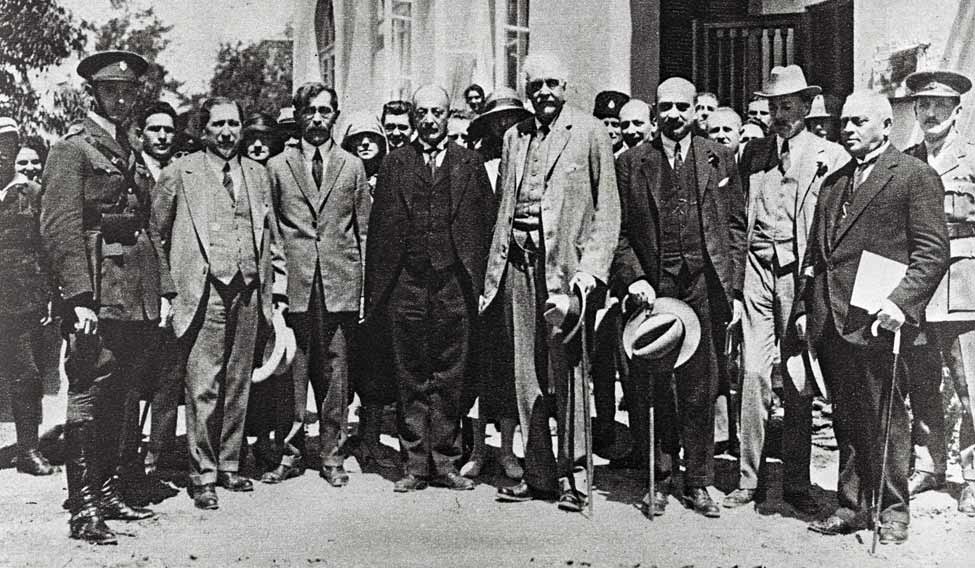

Britain, by far, was the most sympathetic European country to the Zionist cause so it was natural for the Zionist leaders to concentrate their attention on London. Moreover, Britain was the predominant imperial power, exerting control over nearly a quarter of humanity. Chaim Weizmann, a Russian-born biochemist, who was working at the University of Manchester, took the lead to get the Zionist point of view across to the British establishment. Weizmann had good relations with Balfour and several other members of the British cabinet and he tried his best to convince them about the importance of supporting the demand for a Jewish homeland.

The mandate to take the lead in the process came to Weizmann accidentally. When the war broke out, most luminaries of the Zionist movement were living in Germany and Austria, while a majority of the movement's footsoldiers were subjects of the Russian empire, living in Russia, Ukraine, Poland and Lithuania. To prevent a schism in the Zionist movement, it chose to remain neutral during the war. Subsequently, it diminished the influence of the Zionists in allied capitals like London. But when the Ottomans joined the war on the side of Germany and Austria, Britain devised plans to invade Palestine and Weizmann spotted an opportunity to ally with the British and seek their support for a Jewish state. Britain also calculated that by promoting the Jewish cause, it could attract the support of the Jews for its war efforts.

The decision to support the Zionist demand, however, was not easy for Britain. It required the support of other major global powers as there were very strong anti-Zionist lobbies, including Jewish ones, across Europe and the United States, who staunchly opposed demands for a new state or special privileges for Jews in Palestine. Support from the US, France and the Catholic church was crucial. For this purpose, Weizmann enlisted the support of a Polish Jew Nahum Sokolow, known as the pioneer of Hebrew journalism. A polyglot and a man of impeccable diplomatic skills, Sokolow first charmed the French and got Jules Cambon, the French foreign minister, to write a letter offering support of the Allied Powers [France, Russia and Britain] to the Zionist project of “Jewish colonisation of Palestine”, subject to the “independence of the Holy Places”. Sokolow met Pope Benedict XV in the Vatican and got his support as well, which prompted Italy also to lend its support for the Zionist cause. The pope told Sokolow that the return of the Jews to Palestine was an act of God. It was a far cry from the hostile reception Herzl himself got in 1904 from Pope Pius X.

Arthur Balfour (C), former British prime minister, and Chaim Weizmann (3rd-R), the then future first President of Israel, visiting Tel Aviv. This handout file photo taken in 1925 was obtained from the Israeli Government Press Office | AFP

Arthur Balfour (C), former British prime minister, and Chaim Weizmann (3rd-R), the then future first President of Israel, visiting Tel Aviv. This handout file photo taken in 1925 was obtained from the Israeli Government Press Office | AFP

The final assent had to come from the United States. By April 1917, the US had formally entered the war in Europe by declaring war on Germany. To get the approval of President Woodrow Wilson, Sokolow approached one of his friends, Louis D. Brandeis, an associate judge of the Supreme Court of the United States. Son of Jewish immigrants from Bohemia (in present-day Czech Republic), Brandeis served as the president of the Provisional Executive Committee for Zionist Affairs. He had the ear of President Wilson, and despite the opposition of the American policy establishment towards political Zionism, he managed to get the president's imprimatur—although it had to be kept as a secret till August 1918—for setting up a Jewish state in Palestine.

Armed by the endorsements, the British Zionists moved fast, and got Lord Balfour to issue the declaration. Two years later, when the Versailles Peace Conference was launched by the US, Britain, France, Italy and Japan, the victors of the World War, to set the terms of peace for the defeated Central Powers, the Zionists presented the Balfour Declaration and it was made a part of the Allies' postwar declaration. In April 1920, at the San Remo Conference in Italy, the allied powers finalised the mandates—territories of the Ottoman empire which would be assigned to the victors to administer as trusts on behalf of the League of Nations—and the Balfour Declaration was written into the order of the League of Nations assigning the mandate of Palestine to Britain. Thus, from a private guarantee, the Balfour Declaration became part of international law. And, in less than three decades, the state of Israel declared independence, establishing a sovereign nation for the Jews across the world.

For the Arabs, the Balfour Declaration has been the “original sin”. No wonder, Mahmoud Abbas, president of the Palestinian Authority, called upon the British government to apologise for the declaration, instead of celebrating its centenary. “Lord Balfour promised a land that was not his to promise, disregarding the political rights of those who already lived there,” wrote Abbas, in an op-ed for the Guardian. “The Balfour Declaration is not something to be celebrated, certainly not while one of the peoples affected continues to suffer such injustice. The creation of a homeland for one people resulted in the dispossession and continuing persecution of another, now a deep imbalance between the occupier and the occupied. The balance must be redressed.” Thousands of Palestinians in Ramallah, the provisional headquarters of the Palestinian Authority, marched on November 2 to the British consulate there, raising slogans against the declaration.

British Prime Minister Theresa May, however, celebrated the centenary of the declaration on November 2 in London, in the presence of Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu. She said there could be no excuses for any kind of hatred towards the Jewish people and that criticising Israel could never be an excuse for questioning Israel's right to exist. “Britain is proud of our pioneering role in the creation of the state of Israel,” she said. May and Netanyahu were hosted by Baron Jacob Rothschild, grandnephew of Baron Walter Rothschild at a gala dinner held at Lancaster House in London.

British Prime Minister Theresa May shakes hands with Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu at a meeting in London | AP

British Prime Minister Theresa May shakes hands with Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu at a meeting in London | AP

British opposition leader Jeremy Corbyn, a longtime critic of Israel, chose to skip the dinner. In a statement, he called upon the May government to recognise Palestine. “Balfour promised to help establish a national home for the Jewish people in Palestine while pledging that nothing would be done to prejudice the rights of its existing non-Jewish communities. A hundred years on, the second part of Britain's pledge has still not been fulfilled,” wrote Corbyn.

A century after it was signed, the Balfour Declaration continues to divide the world. And, a solution is nowhere in sight.