The just concluded summit-level visit of Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe to India and the use of the phrase “growing convergence” in the joint statement in relation to the political, economic and strategic of the two Asian democracies will have a bearing on China’s hegemonic ambitions for the extended Asian region.

Over the last year, particularly in the Obama-Trump transition, Beijing has been more assertive than before in establishing its hegemony in the region. The South China Sea (SCS) international tribunal award is case in point. China rejected the ruling that was derived from the principles embedded in the UNCLOS and extended its territorial claim though the artificial islands it had constructed.

Having established its hegemony in the SCS through muscular means, the next objective was to seek compliance from its principal interlocutor, in this case Philippines. The change of political leadership in Manila led to a dramatic volte face and the ripple effect in ASEAN was evident. The sub-text seemed to suggest that China ‘gets what it wants’ and that this hegemonic pattern would remain unchallenged.

C. Uday Bhaskar | File

C. Uday Bhaskar | File

However, the Doklam face-off over disputed territorial claims that involved Bhutan, China and India in June, and its subsequent resolution—even if temporary—have provided a different template to the SCS trajectory. It may be recalled that during the Doklam tension, the Japanese position was supportive of India and this again was a subtle signal to Beijing.

Thus, it is instructive to note that in the September 14 India-Japan joint statement “the two prime ministers affirmed strong commitment to their values-based partnership in achieving a free, open and prosperous Indo-Pacific region where sovereignty and international law are respected, and differences are resolved through dialogue, and where all countries, large or small, enjoy freedom of navigation and over-flight, sustainable development, and a free, fair, and open trade and investment system.”

While there is no specific reference to the SCS, the mention of the Indo-Pacific continuum is adequate—for it subsumes the entire western Pacific maritime domain and Beijing would have noted the import of the semantic choice. Furthermore, in the opening section of the statement, it is asserted that “the two prime ministers underlined that India and Japan could play a central role in safeguarding and strengthening such a rules-based order.”

The need to evolve a rules-based order in the latent anarchy, which is the central motif of international relations, remains an abiding challenge. In the more recent phase of global history, post World War II—the US-led western alliance with its commitment to the liberal, democratic principle prevailed and provided a kind of ‘consensual hegemony’—more so after the disintegration of the Soviet Union—which became ‘former’ in December 1991.

China, which benefited from this US-led rule-based order, is now on the ascendant and is the number two GDP nation. It will in all likelihood overtake the USA to be the number one GDP within the next decade and is determined to recover its lost preeminence before 2049—when Beijing will celebrate the centenary of the birth of modern China with its communist pedigree led by Chairman Mao.

The hegemonic aspiration of the emerging power that seeks to displace and replace the status quo is part of the historical rhythm from ancient times to the current century. Beijing’s aspirations are almost predictable.

However, it is my assessment, at this stage, that the hegemonic aspirations of China will not go unchallenged. The India-Japan joint vision—as reflected in the joint-statement details a certain bi-lateral intent.

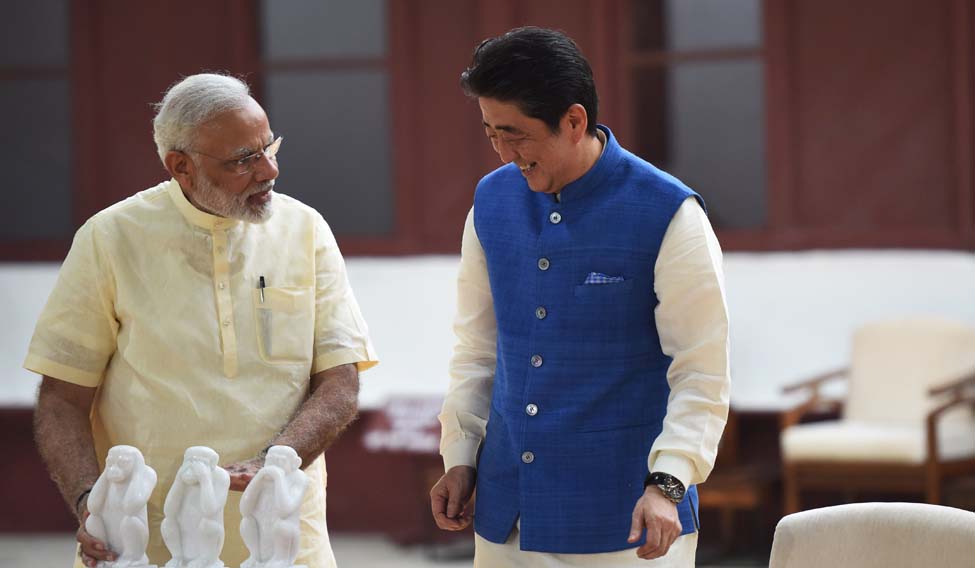

The degree to which this is realised will depend on a complex set of factors, including the domestic political support for the two prime ministers—Abe and Modi—and the manner in which the USA and Russia will position themselves in relation to Beijing after the October Party Congress.

Watch this space!

(The author is director, Society for Policy Studies, New Delhi)