The season of IFFK introduces film buffs to a host of unfamiliar stories, people and experiences and urges them to accept these not at their face value, but with great caution. The film festival is far from normal as movies cease to become mere tools of entertainment, instead assumes the role of a communicator who speaks of things known and unknown. However, as the curtains come down on the festival, we are overcome by the need to fall back to normalcy.

The IFFK had made an attempt to unravel the theme of women in cinema through one of the segments of movies screened. More often than not, cinema reduces women to becoming eye candies or employ female characters merely to cater to the need of being the love interest of the protagonist.

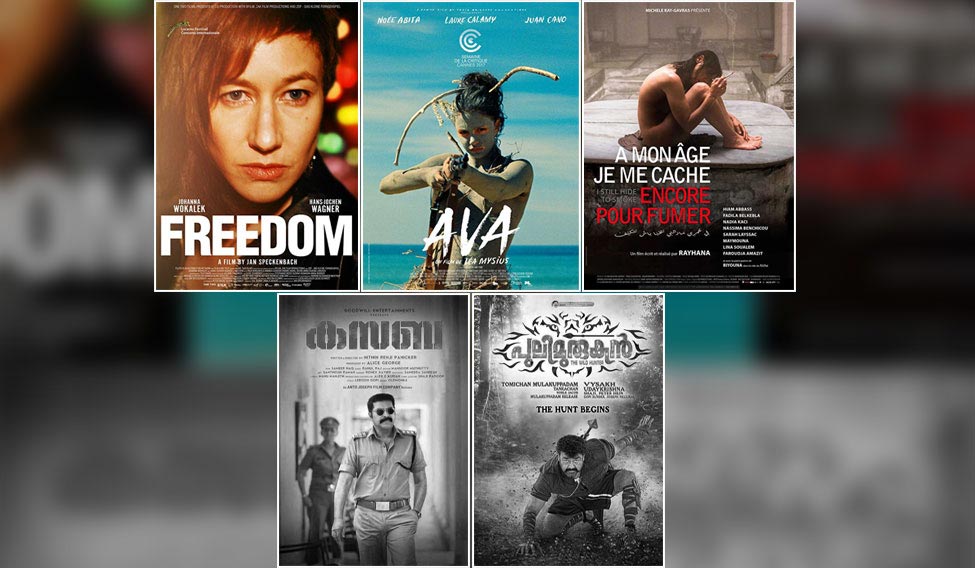

The woes women face are strangely similar in all over the world; their difference lies only in the degree of problems and not the problems themselves. Whether it is religion, government, or the male agents of patriarchy, the quest is ever them same—to reduce women to their physical being and take control of their bodies. Whether it is a teenager revolting against a system that tries to take away her freedom (Ava), or a woman resigning from her duties as a mother and wife (Freedom), or a group of women sharing their pain in a private space in the absence of men (I Still Hide to Smoke), the stories they speak are all the same.

The ultimate struggle of women to regain control over their bodies, ascertain their rights as individuals, and excuse themselves from the ‘duties’ forced on them by the system, might seem interesting as we watch them on screen, as we see them happening far away from us even as the men mouth a silent thanks to the benevolent Indian society for creating a system where women are morally guarded.

As an unwanted pregnancy results in the state forcing Ava’s parents to come together, it leads to both of them trying to escape the reality. Ava’s father works far away from home, leaving all duties of raising his daughter to his wife, and this results in him blaming his wife for all things concerned with Ava. Ava’s mother, meanwhile, imposes restrictions on her daughter because she fears that Ava might end up becoming like her. The husband and wife act as if they love their daughter, but everything they do result in Ava saying she cannot be loved because she was never wanted. As the state enforces their rules on a woman’s body, they don’t seem to care about the psychological impact they create, as if somehow the ‘sanctity’ of human life is only limited to their body.

A similar and many other stories are told by the women of I Still Hide to Smoke. But this is not one or two stories, and they are not dissimilar in other countries as well. There is a woman married at the age of 11 and the film discusses how the society finds the marriage normal. The women gathered with her are sympathetic, but there are only women and they are merely sympathetic. Another woman, who secured freedom from her in-laws by way of divorce, is criticised by some, but not exiled, mainly because of the fact that they believe that if they don’t stand up for each other, no one else will.

Freedom is about a woman, a mother and wife, who, one day, decides to set herself free from these 'roles'. The camera follows the woman wandering through the streets with no definite plan, and a family torn apart.

These movies do tell IFFK's readiness to explore the theme of feminism in films. But Sadaf Foroughi, director of Ava, and Reyhana Obermeyer, director of I Still Hide to Smoke are both female directors exploring female issues, while Jan Speckenbach who helmed Freedom is a man.

In Malayalam movies too, there has been occasional films exploring women and their issues— Padmarajan did it in Desatanakkili Karayarilla and I.V. Sasi in Avalude Ravukal. However, it is important to look at how many female directors have explored the issues in the industry. Whether Anjali Menon discussing the same in Manjadikkuru or Revathi dealing with it in Mitr, My Friend, it is important to realize that hardly any films talk about women at length.

A while ago, Shani Prabhakaran, a journalist, pointed out the blatant sexism in the Malayalam film Pulimurugan and received a lot of sexism in return. Somehow, most people found the reaction of fans who trolled her endlessly, normal. Not justified, but normal nonetheless. There was also the recent case of another actor, Parvathy, being abused online for her criticism of the misogyny Mammootty's character portrayed in the movie Kasaba.

Pulimurugan, Kasaba and the like—these are our movies, movies we watch, the characters we applaud. This is the normalcy that the audience need to return to. The fandom, the glitz, glamour, stars, fame, and of course the misogyny. The misogyny in movies is forgiven, not just by fans alone, but by most men (yes, men) as they feel that this a part of the society and hence it is okay to visualize it.

For a week, movie lovers come together to celebrate the influential, magical medium of cinema, to be part of a movement for the betterment of movies. But soon this is forgotten, and we go back to what is deemed normal in cinema. It is this normal that scares me.