It’s been a long journey for Shanker Raman in films. Raman was busy with his studies—Physics at Delhi’s St Stephen’s College—till the time his brother gifted him a digital camera. The 42-year-old award-winning cinematographer, screenplay writer and now a director, says that he took to photography instantly, like fish to water. “There was a dark room in college. I was not just interested in taking pictures, but was very fascinated by developing an image, too. Every single aspect of photography fascinated me a lot. I, kind of, benefited from having an access to the processing of photography at a very subsidised rate. That began the entire journey. I got interested in filmmaking eventually and applied to Film and Television Academy of India and luckily got through to it too,” he recalls.

Raman’s choices have been eclectic, and yet each of the films he has been associated with, questions societal norms. Whether it be his first film as a cinematographer, Frozen (2007), which was the story of a family in the Himalayas affected by the activities of the armed forces and also won him the National award for Best Cinematography, or the later films like Harud (2013) dealing with the Kashmir conflict for which he even co-wrote the screenplay. The Great Indian Butterfly (2007) is about a modern couple’s search for self-discovery, 2010’s Peepli Live dealt with farmer suicides, while 2014’s Fireflies about two chalk-and-cheese brothers delved into the intricacies of relationships. Raman says he has been happy with the conscious choices he has made in his career. “I have had the privilege of associating with people who are very talented and of independent thinking. And also, you know, when I say independent, it shouldn’t sound like snobbish. The idea of independent is to find a way to express yourself in a way that is different from the way the mainstream does,” he says.

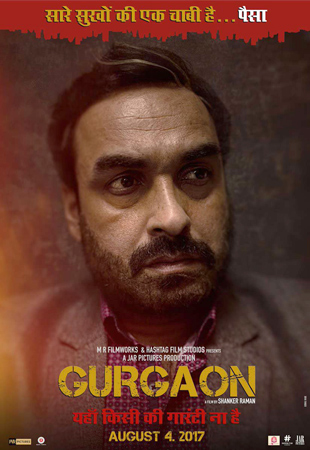

In his debut film as a director, Gurgaon, a noir that questions gender politics, and how power works in families, Raman tells the story of a brother-sister rivalry (starring Akshay Oberoi and Ragini Khanna). Here, he talks about the film, the work that went into it and more. Excerpts:

What was the idea of using Gurgaon as your film’s theme?

Gurgaon is a city that has come up in the last two-three decades. When I say Gurgaon, everyone has his or her own impression of it. I don’t have to describe it; we have a more vivid imagination of Gurgaon that I can ever provide. In that sense, it was a title that made sense. It attracts attention to the story of a family that lives there and has contributed to the ever thriving real-estate business. You are already looking at the vulnerability of this family. It’s about urban alienation and violence. Gurgaon has a context to the story, and the title only made sense.

The film has taken a long time—you started working on the film in 2012. What were the roadblocks?

Roadblocks, primarily, was financing. We had an investor with whom we started the project and subsequently he withdrew from the project. It was stalled for almost a year before another bunch of investors showed interest. And then, he wanted to relook at the whole material in a brand new way and that again it didn’t work out. After almost a whole year, Ajay (G. Rai, Jar Pictures) and I decided to go ahead and make it. We figured out a team and started working on it. Somewhere, we knew that this is a mainstream film. In the sense that whatever money people are going to invest must recover and there must be some sort of accountability to it. It’s not like that if we don’t make money, it’s going to be okay. We were very mindful of that. We wanted to make sure that we have something that will give results. So, it took time to get there. It didn’t take time because we needed time.

But were you prepared for all of this?

Umm. I am prepared for the unexpected, yes. But this is not what I was expecting (laughs). If someone had told me in January, 2012, that it will take so much time, I would have been like ‘what are you saying?’ That was the month my daughter was born so I know the film is as old as her. You cannot be prepared for this, you can only be prepared when you are doing something real, tangible. Also, the writing process cannot happen endlessly. The writing process can only be converted, once you are actually ready to make the film. You can only write up to a point. After that, you have to look at the casting, the production, which also influences the writing. The writing shifts on the basis of that.

And also, since you have used Gurgaon as a metaphor, which has also changed or evolved in many ways, did that bother you?

No, not really. Gurgaon is exactly what it is, a city that grows like any other city.

A genre film like yours, which is a noir, makes it easy to layer it with messages. Were you looking at something in particular?

I don’t know if I am trying to send out a message. But what I would say is that the foundation of the film is based on human drama and human conflicts or ambiguities. It comprises of stuff that we pretend to hide. It’s all part of a human condition. In that sense, it’s relevant to all of us. When you follow the story, you will feel that there’s a Gurgaon, not geographically, everywhere. We all complain about the environment we live in—there are gender issues, political issues or social issues. The point is, are we prepared for a transformation, how can that transformation be brought? When I say transformation, I mean inventing something new, something from the scratch. As a society are we ready to lay that foundation? I don’t think I wanted to underline this as a message; it’s just something to think about.

Also, as a genre, noir is underexplored in our country. As a filmmaker what do you think is the reason for that, and how did you get interested in the genre?

See, I don’t know the answer to the first question. But I didn’t explore Gurgaon as a neo-noir to begin with. The way the film was built and formed, and the colours and the whole structure, was devised on a place that was very murky. It’s unclear, what is right or wrong, good or bad, everything seems to be grey. And everything seems to be as inconclusive as each other. And yet, there is a strong sense of character. You can’t explain it, but you are, may be at times, afraid of it because it’s unfamiliar. You know, when you are looking at a space where people are hiding most of the times—hiding from who they are, what they have done or what they intend to be—to describe that environment, you think that this should be the colour palette, this should be the treatment. It just happened to be noir, it wasn’t intentional. Noir is also representation of what I am drawing your attention to, and I am drawing your attention to what is not seen.

More than noir, I would say I had a sense of western in mind. Making Gurgaon also felt like making a western because a western is set in a landscape where people make their own rules.

The script was also part of the NFDC’s Work In Progress Lab (2015). How did that help?

I had some phenomenal mentors inside one room like Olivia Stewart (producer and script consultant), Marco Mueller (producer, Festival Director of IFFA Macau) among others. To be qualified for the Work In Progress Lab is a big thing because there only five or six films that they choose. They took me through a very specific process that helped me look at my own material very objectively. More importantly, my editor (Shan Mohammed) was also there. We went through the process together. I would specifically like to mention Shan’s effort because the way he cut the film eventually... his contribution is huge. He is the one who kept the whole narrative together. Despite my deviating and jumping from one place to another, he is the one who kept the integrity of the thought process intact in the material. Since we were together with the mentors at the lab, we could see where we were losing the plot. I would say that process was helpful. When Marco came and chose the film for the Macau Film Festival, he said, ‘I am both shocked and surprised that you actually took our advice’. It took us some time to get there, but we got there.

The film is releasing with a big ticket film (Jab Harry Met Sejal) on August 4. If given a choice, would you have changed the date?

We always had a choice. We could have released it in October, too. There was no pressing factor to come now. I just feel there are certain factors that lead to a film being ready and ready for release. The general perception is that just get done with it once the film is ready. I don’t think we are coming out of insecurity or desperation. This film is also a result of a great collaboration of everybody, especially our producers. And everyone felt that it’s right. There’s this thinking that that a small film will not work with a big film. For example, if we are getting only one show, that too in the morning, that would be a problem. But, if we are getting the shows that we want and reaching out to our audience as well as creating some, there’s no issue.

But have you been able to do that? That was the intention to ask this question. Because a lot of films get a limited release with a big ticket film and even if the content is good, the film loses out in the competition of small and big, alternate and mainstream.

You are talking about a 100-crore film. A film with such a big budget will automatically eat up the news, including political news. There are a lot of factors to it. The other film is one-tenth of the budget. I feel all films will do well if the content is good and it works for the audience. We have the numbers that we are targeting, anything more than that is bonus.

Lastly, what’s the progress on The Trappers Snare?

I have written it, haven’t started working on it yet. It’s a kind of film that starts, stops and starts again. It’s a project that you take time with, a kind of art-house project requiring a particular kind of financing and foreign collaboration to make it happen (it has won the top Open Doors Grant of 30,000 Swiss francs at the Locarno film festival in Switzerland last year). It will have its own journey. It’s set in Sri Lanka in the backdrop of the civil war and tracks the story of a Tamil boy. It’s a coming-of-age story, I would say, of his journey to find peace.