Every five years, the President of India, under the Article 280 of the Constitution appoints a finance commission (FC) to primarily analyse the fiscal structure of the government—both at the Centre and state, developments in the government revenue and expenditures, and the economy. The commission recommends changes in the devolution of the central tax revenue to the states. In our federal structure, the Centre has the authority to levy direct taxes such as income tax and corporation tax, and indirect taxes such as excise duties, customs duties, service tax, and the state governments levy sales tax, state VAT, entertainment tax, luxury tax, entry tax, and tax on advertisement.

The finances of the state governments largely depend on the share of the central taxes and the grants they receive from the Centre. The primary purpose of the FC is to decide on allocation of net proceeds of central taxes between the Centre and the states, between states, and also determine the principles that should govern the grants in aid given by the Centre to the states.

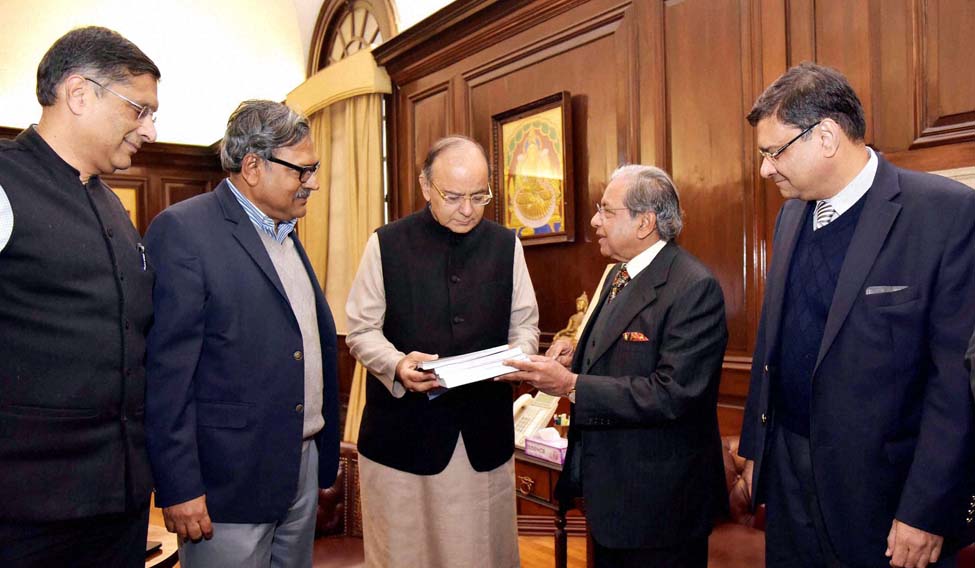

N.K. Singh, former revenue secretary and member of the erstwhile Planning Commission, has been appointed as the chairman of the 15th FC. However, this commission’s task is different and more comprehensive than the previous commissions for two reasons.

First, GST, which has changed the structure of indirect taxation in the country, is in its first year of implementation. Second, the terms of reference of the FC cover the entire fiscal system and its functioning and are more wide-ranging than any previous commissions.

In addition to its usual task of determining the Centre’s tax revenue allocation to states, the 15th FC has been asked to review the current status of finances, deficits, debt levels and fiscal discipline efforts of both the Centre and states, and recommend a fiscal consolidation map for sound fiscal management guided by the principles of equity, efficiency and transparency. This marks a departure from the past, and the new FC will have to make critical reviews of both the Centre and state-level fiscal structures and trends therein to recommend measures for more efficient fiscal consolidation. The additional task might engage the FC into an exercise towards a new fiscal policy, and a review of direct taxation system, now that a new indirect tax structure is in place.

The 14th Finance Commission gave a big bonanza to the states by raising the share of states in net central taxes to 42 per cent from 32 per cent after ending discretionary resource transfers from the Centre to the states. The distribution of the tax pool of the states among individual states is guided by a formula of weighted average on four data figures—population (17.5 per cent in 1971 while 10 per cent in 2011), fiscal capacity/income distance (50 per cent), area (15 per cent) and forest cover (7.5 per cent). The new commission may change these weights or bring in new factors. The idea of this formula is to allocate resources to states based on their physical size, population needs, their fiscal capacity, need for central support, and how they manage their finances.

Until the onset of GST this year, the main source of tax revenue of the state governments was the sales tax. The GST has been a major structural change in the indirect taxation of goods and services replacing the multiple taxes at different levels that had a cascading effect on costs and prices. The new commission will have to determine and fix a new benchmark for the sharing of GST between the Centre and the states.

One of the major reasons for opposition by the states for the adoption of GST, despite its tremendous economic benefits, was that it impairs the federalism by imparting greater power to the Centre in levying taxes. Hence, the commission faces with a fresh challenge of reviewing the state finances where they have lost their fiscal power. It also has to look at the progress of the GST collection before it decides its allocation formula.

The loss of revenue due to GST for the states is estimated between 46 per cent to 55 per cent and the revenue from the subsumed taxes grew at 14 per cent between 2012-16. The states' GST share has to not only take care of the loss, but also compensate them for the annual growth in revenue they realise.

What is the fiscal arithmetic that the FC has to deal with? During 2016-17, India's GDP was Rs 152 lakh crore. The central government tax revenue (net) amounted to Rs 10.8 lakh crore. The states collected taxes of up to Rs 10.1 lakh crore and received Rs 5.8 lakh crore from the Centre as their share of central taxes. The Centre spent Rs 20 lakh crore and states Rs 27 lakh crore, which amounts to 30 per cent of the GDP.

The commission faces an uphill task to deal with these broad numbers and work out ways in which it can improvise the fiscal system to make it more efficient, equitable and conducive to growth.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the publication.