In his three months in Mumbai, Devesh Kumar Yadav has seen the Gateway of India, Haji Ali Dargah, Siddhivinayak Temple and Swami Samarth Math. The list may seem short, but it is longer than those of others like him, who travel thousands of kilometres for medical reasons. Devesh, from Gaya, Bihar, has lymphoma and is currently undergoing treatment at the Tata Memorial Hospital. A class 12 student who plans to study arts, Devesh is waiting to finish his chemotherapy cycle to return home.

It all started with a tumour on his neck, which the doctors in Bihar diagnosed as tuberculosis. For two years, Devesh was treated for tuberculosis, but the tumour kept growing. Finally, someone in his village said he should go to Mumbai. Once there, finding a place to stay was a task. However, Devesh, with his elder brother, Shailesh, found accommodation in Sant Gadge Maharaj Dharamshala Trust, which provides rooms at Rs 120, along with free meals for the patient and relatives. The family, which had already spent Rs 2 lakh for the tuberculosis treatment, spent Rs 50,000 in Mumbai. Fortunately, some trusts helped them raise another Rs 1.5 lakh. “We are satisfied with the treatment and the doctors are wonderful,” says Devesh. However, he is worried that he may get an infection as there is construction going on at the trust's building. “We don’t know how long I will be in Mumbai, it will be three or even four months. With cancer, you can’t say,” he says.

The Jaiswal family stays in a room on the first floor of the same building. A clothes line runs across the room; medicines, cookware and belongings are scattered on the floor. Manoj Jaiswal and his wife came to Mumbai to find a cure for their five-year-old son Krishna's blood cancer. Manoj owns a restaurant in Jalna but, since the diagnosis, five months ago, he shut it down. The family raised Rs 3 lakh through various trusts and spent Rs 40,000 from their pockets. “He sometimes has fever at night and we have to rush to the hospital. But, it sometimes takes up to 12 hours before the doctors can see him,” says Manoj.

There are several others like them. In fact, National Sample Survey Office data on domestic tourism says the majority of overnight trips made by Indians are for health and medical reasons. The share of health-related trips from rural areas (48 per cent) was nearly double of the same trips from urban areas (25 per cent). This points to the lack of good health care infrastructure in the interiors of the country.

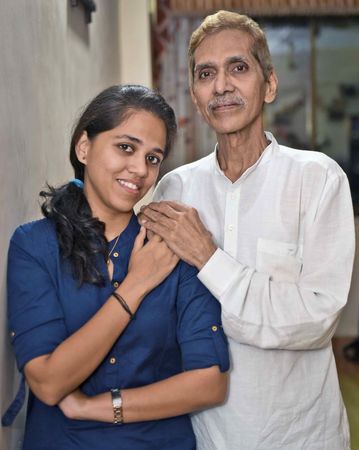

Sanjay Raut with his daughter, Kranti | Amey Mansabdar

Sanjay Raut with his daughter, Kranti | Amey Mansabdar

The data also shows that the average expenditure for such overnight trips was Rs 15,000. “Access to health care is a difficult situation, which forces people to come from districts to the cities,” says Dr Sakhtivel Selvaraj, a health economist with Public Health Foundation of India, Delhi. “Studies show that they spend almost 8 to 9 per cent of their cost of treatment on the travel alone. There is also loss of income for the person who accompanies the patient, along with the cost of lodging for them.” This lack of access and cost of travelling could also be forcing many to not seek treatment at all.

Meanwhile, for those who travel, grappling with the diagnosis, finding a hospital and affording the cure, all without support, can be an uphill task.

However, many hospitals, which see a large number of patients from outside the state, help them solve at least some of these problems. For instance, Hyderabad’s L.V. Prasad Eye Institute provides free treatment for poor patients. Almost 70 per cent of the institute's patients come from other states, says Dr Swathi Kaliki, head, The Operation Eyesight Universal Institute for Eye Cancer at LVPEI. She says most patients are referred to them by other specialists—as the cases are complicated—or come to them after hearing about their specialisations and state-of-the-art facilities. The hospital provides free accommodation for patients for the first two to three days, within the hospital campus, along with free meals. If treatment requires more time, they refer patients to places that charge nominal rent. Also, there are some organisations that provide free accommodation to needy patients. “When they return home after the surgery, we give them a reference of a local doctor, who has trained in LVPEI, so that they can go to him for regular screenings or suture removal,” says Kaliki. “They need not come all the way here unless it is important.” Considering India’s huge population and disease burden, each state requires speciality and superspeciality on the lines of LVPEI, she says.

When Sanjay Raut, 56, went to Chennai from Mumbai, three years ago, he only wanted another chance at life. He was suffering from hepatitis C infection, which had led to liver failure, and he was told he had only months to live. “I went to many specialists and doctors and was told that only a transplant can help me,” he says. “One specialist said if I get a transplant from a hospital here (Mumbai), both the donor and the recipient may not survive.” The options given were Bengaluru, Hyderabad, Delhi and Chennai. Raut chose Global Hospitals in Chennai. Though Tamil Nadu has a robust cadaver donation programme, Raut’s condition meant he couldn’t wait and needed a live donor as soon as possible. With his younger daughter, Kranti, 20, as a match, he underwent a liver transplant.

The Rauts had to stay in Chennai for almost three months and Sanjay stayed at a service apartment on the campus. “Our stay was comfortable and I was impressed by the kind of care provided,” says Raut.

Hard times: Devesh Kumar Yadav | Amey Mansabdar

Hard times: Devesh Kumar Yadav | Amey Mansabdar

Mohammed Farouk, deputy general manager at Global Hospitals, is the one who takes care of the patients before and after the transplant. From helping patients settle in a new city to taking care of their needs and keeping their morale high, he and his team make sure the patient feels confident of the procedure. “Patients come to us when they have no choice, they are sick and have little time,” says Farouk. “We do our best to take care of all of their needs and to keep them engaged.” They provide service apartments on the campus, have cafes and restaurants with a lot of cuisines and provide support and care after the surgery.

Along with hospitals, some individuals, too, are doing their part in helping patients. Take, for instance, 54-year-old Suresh Agarwal from Mumbai. Though a successful businessman, who deals in polymers, most people know him as the man who puts a roof over the heads of cancer patients. For the past 15 years, Agarwal has lent his two flats in upmarket Kandivali to cancer patients and their families, for free. The flats have provisions for cooking, a fridge and a television. “After five of my close relatives suffered from cancer, I visited P.D. Hinduja Hospital almost every other day and noticed the plight of the people struggling to fight cancer and make ends meet in Mumbai,” he says. “That is when I decided to lend my flats for the cause.” At any given time, there are usually 15 to 20 people, mostly from Assam, Bihar and West Bengal, living in his flats. “Even educated people think their children will get the disease from these children with cancer, which is a myth,” he says. “Another is that cancer cannot be cured. I wish people supported the patients and helped them fight the stigma.”

For the past four months, Ritik Gupta, 15, and his cousin Alok Gupta, from Madhya Pradesh, have been living in Agarwal’s flat. Ritik is undergoing treatment for acute lymphoblastic leukaemia at P.D. Hinduja Hospital. The early symptoms were fever, joint pain and swelling, and he was diagnosed with malaria. It was after he was admitted to Wockhardt Hospital in Nagpur that he was told it was cancer; he was advised to go to Mumbai. “We didn’t go to Tata Memorial because his condition was serious and we couldn’t afford to wait,” says Alok. “We brought him to Hinduja and he was treated by Dr Sachin Almel.” Ritik recently completed the third of the six chemotherapy cycles and is studying for his class 10 examinations, which he couldn't appear for last year. “While the initial days in Mumbai were difficult, the city has been helpful,” says Alok. “From boarding trains to helping us get funds, people have been helping us.”

Helping hand: Suresh Agarwal (right) with Ritik Gupta | Amey Mansabdar

Helping hand: Suresh Agarwal (right) with Ritik Gupta | Amey Mansabdar

Unless the health infrastructure across the country improves, health-related travels would remain common. Also, as more than 70 per cent of health care in India is out of pocket, seeking treatment is all the more expensive. We also need universal health care so that each citizen can avail the benefits of good care. “Out of the 1.2 billion people, about 400 million are living below poverty line, but the ones who are in the middle income group bracket are also equally vulnerable and can’t afford treatment,” says Selvaraj. “So, a move towards universal health care is needed at the earliest.”